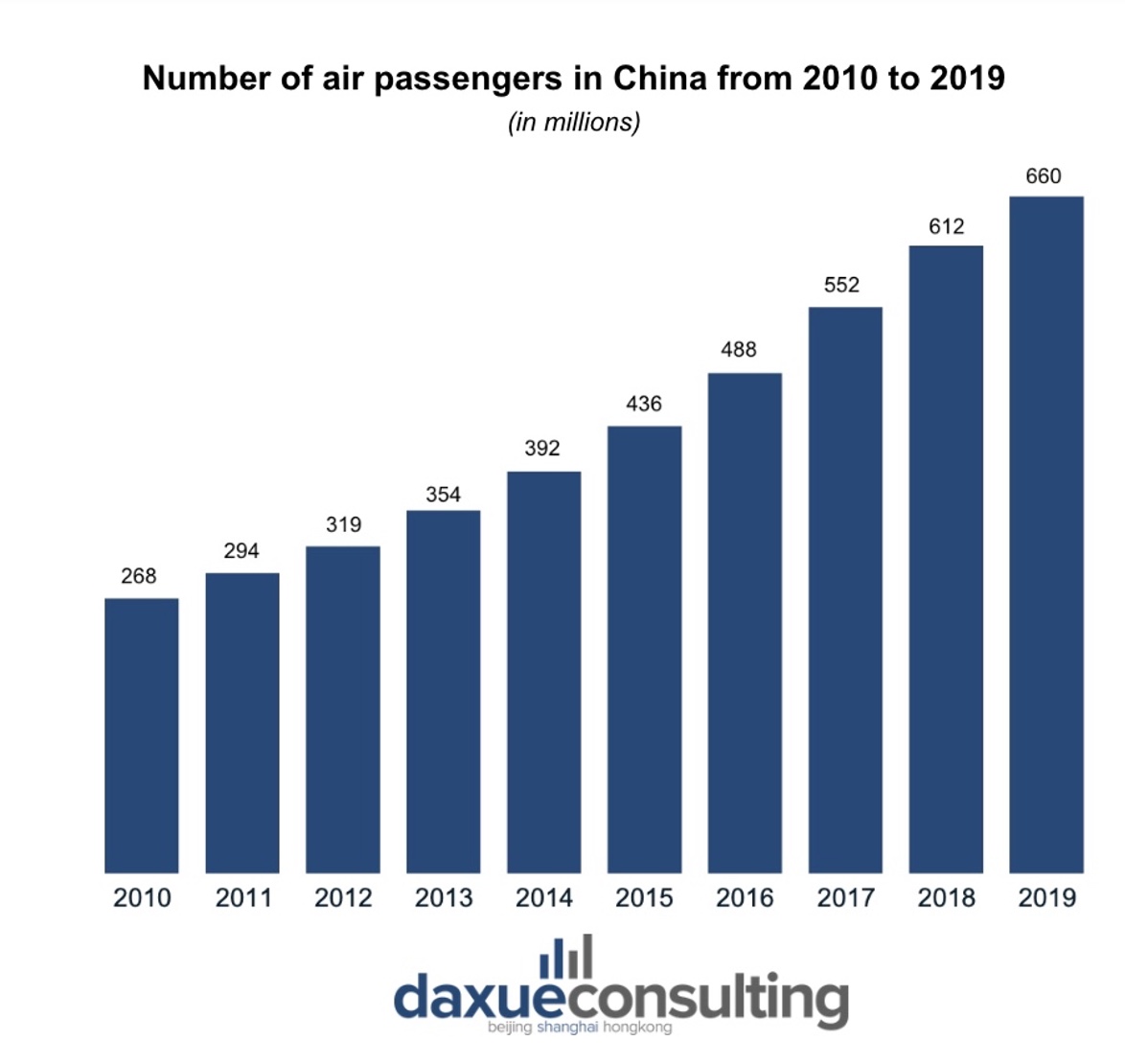

The Chinese aviation market is rapidly growing, boosted by a rising middle class and government support. With an average yearly growth of 10.5% over the past decade, as per the International Air Transport Association (IATA), China surpassed the U.S. as the largest aviation market in 2019 based on passenger numbers. To meet this demand China had constructed 241 airports by 2020 and aims to construct many more to further connect its most peripheral urban centers.

Download our report on Gen Z consumers

The sector’s growth in China offers investment and innovation opportunities, attracting Airbus and Boeing. Since 2008, Airbus has expanded its Chinese presence by assembling its A320-family planes in Tianjin. Boeing, however, mainly assembles in the U.S., with limited Chinese expansion, except for assembling the 737 at its delivery center in Zhoushan.

China takes flight: the domestic manufacturing boom

Homegrown giants: China’s emergence in aircraft production

Over the past decade, China has developed its state-owned aircraft manufacturer, COMAC, to reduce dependency on Western manufacturers. Since 2010, the company has invested heavily in R&D, focusing on jet engines and avionics.

COMAC’s first commercial jet, the ARJ21, launched in 2016, marked China’s entry into the commercial aviation industry. Designed for regional travel, it seats 78-90 passengers and has a range of 2,225 to 3,700 kilometers. However, the ARJ21 wasn’t intended for massive scaling or high returns. COMAC’s major challenge to Boeing and Airbus began in 2010 with the C919, designed to seat up to 168 passengers. The C919 aims to rival Boeing’s 737 Max and Airbus’s A320neo.

Additionally, COMAC is developing the CR929 with Russia’s UAC. Initially scheduled for delivery in 2023, sanctions on Russia have forced both manufacturers to redesign the model with components exclusively sourced in China and Russia. Its first deliveries are now expected in the late 2020s.

Collaborative horizons: global partnerships and progress

In the C919’s early stages, COMAC sought foreign expertise and collaboration to develop a competitive airplane and establish its supply chain. COMAC worked with over 200 companies and 20,000 experts globally.

In March 2012, COMAC started a strategic partnership with Bombardier Aerospace, focusing on supply chain and flight training. COMAC also collaborated with global aerospace companies for the C919’s avionics and systems. This includes Honeywell for the flight control system and Collins Aerospace for navigation. It sourced various components globally, like Liebherr (Germany) for landing gear and Parker Aerospace (USA) for hydraulics.

COMAC also works with universities and research institutions for technology advancement. In March 2023, it partnered with The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU) by signing a Memorandum of Understanding to collaborate on civil aviation technology in China.

Pandemic turbulence and China’s aviation comeback

Reinventing in crisis: adapting to COVID-19 challenges

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted the global aircraft industry, causing a downturn that may need three to five years to recover. China’s aircraft manufacturing, including Boeing and Airbus operations, was also affected, though differently.

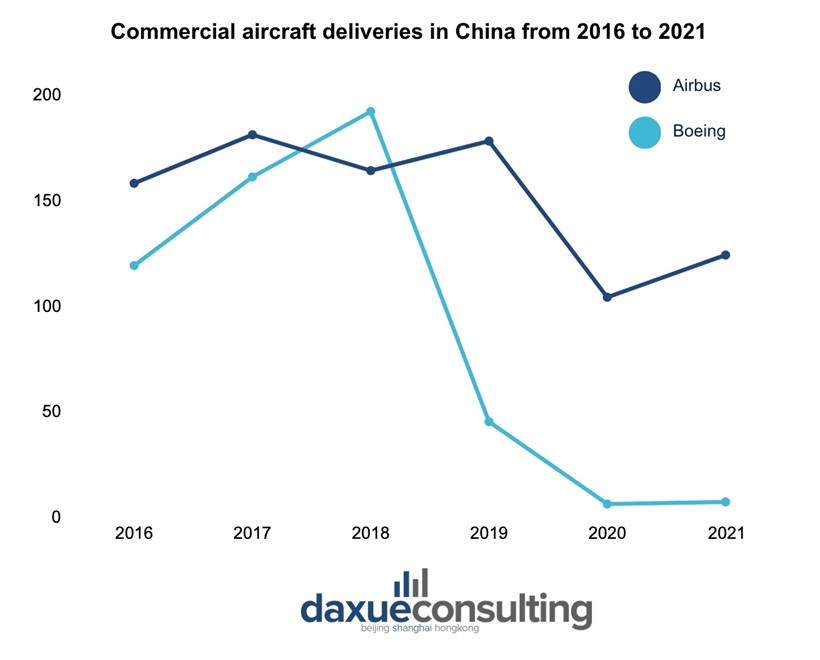

Despite pausing production in France and Spain, Airbus managed to maintain a positive trajectory in China. On the other side, Boeing faced more challenges, worsened by the pandemic. Already struggling with decreased sales in China due to the grounding of the 737 MAX following two crashes, COVID-19 led to delays in 777X plane deliveries from 2022 to late 2023 and further financial issues.

COMAC’s research and assembly were disrupted too. Yet, China used this situation to challenge the global aviation manufacturing duopoly. The government supported COMAC by pushing its three major state-owned airlines to postpone over 100 aircraft deliveries from Boeing and Airbus while maintaining orders from COMAC.

Building back: recovery pathways and strategies of the Chinese aviation market

The COVID-induced slump in China’s internal demand recovered quickly after travel restrictions were lifted. By July 2023, China’s narrowbody and widebody jet fleets had grown by 18% and 26%, respectively, compared to July 2019. However, this recovery wasn’t uniform across manufacturers. Airbus, with its A320neo, A321neo, and A350-900, gained most from the upswing, while US-China tensions limited Boeing’s market access.

Post-COVID, Airbus plans to double its Tianjin assembly line production from 2023, highlighting its increasing influence in China. Despite facing greater challenges, Boeing still values China as a key market, having delivered until now over 2,000 planes to Chinese airlines and leasing companies.

While both Airbus and Boeing have opportunities to grow in China, it is important to note a decline in Chinese orders for Western jets. Chinese carriers’ demand began falling after 2014, with orders flattening by 2018 in favor of COMAC. Thus, while both companies have significant existing pipelines, future substantial revenue growth is not assured.

Navigating new skies: market dynamics and opportunities in Chinese aviation market

Inside the domestic surge: demand and supply shifts

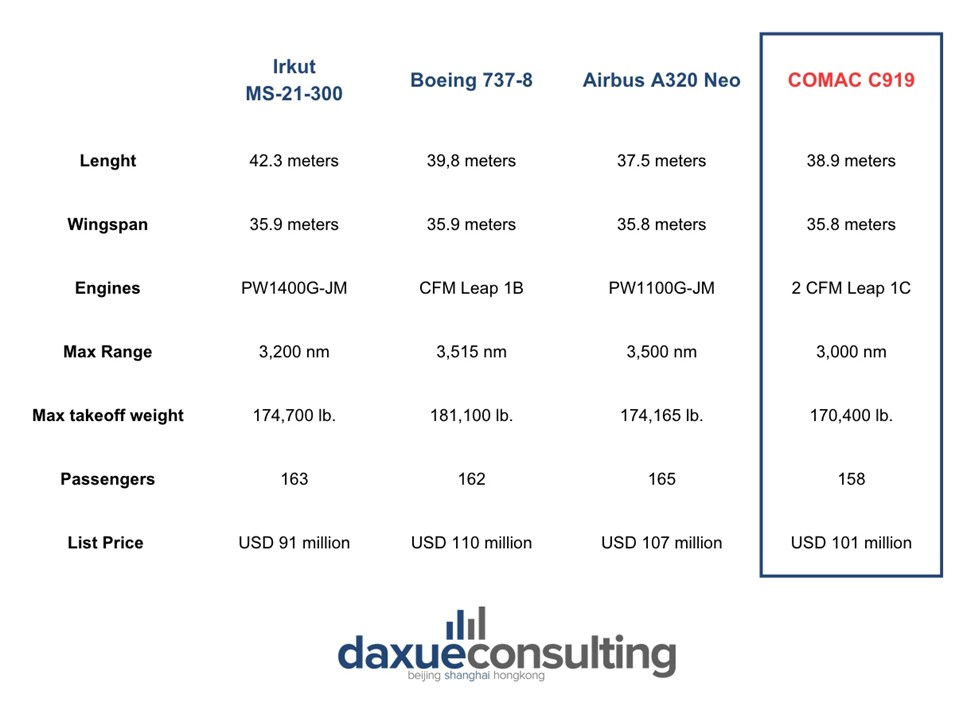

In May 2022, after significant alterations and improvements to the aircraft, the C919 completed its first pre-delivery flight test at Shanghai Pudong International Airport. The C919 was finally commercialized at a selling price of RMB 653 million (equivalent to USD 101 million), closely aligning with the cost of its competitors, the Airbus A320neo and the Boeing 737 MAX. The cost doubled compared to the initial expectation of US$50 million. This increase is attributed to additional components, such as composite wings, which were not initially predicted for this model by the manufacturers.

As of now, COMAC has received about 815 commitments for the C919 from 28 Chinese airlines and domestic leasing firms. According to Cirium’s Fleets Analyzer, the majority of COMAC orders come from China’s three major airlines, Air China, China Southern, and China Eastern. No airline from outside of China has yet to place a direct order to buy the plane.

Yet assembly lines have been relatively slow to kick off production. The first C919 was delivered to China Eastern Airlines in 2022 while only other four aircraft in the first batch of orders have been delivered throughout 2023.

Global ambitions: expanding China’s aviation footprint overseas

As a state-backed company, COMAC has access to the necessary resources to achieve high-level aircraft manufacturing technology in-house. Nevertheless, in the short term, it is believed that Chinese-made jets will still lag behind market standards set by more competitive airplane models offered by either Boeing or Airbus.

As of now, COMAC holds a relatively insignificant share of the global commercial aviation market However, they are making significant investments to increase their presence. Overseas export numbers for Chinese-made aircraft have been for the moment quite modest, with most sales occurring domestically or in developing markets, such as Indonesia, where price competition plays a major role.

However, it is not strategically correct to underestimate China’s ability to penetrate the aircraft market. “The aircraft landscape is likely to shift from a European-US manufacturing duopoly to accommodate a third part, and that’s probably the Chinese.” Shukor Yosof, founder of aviation advisory firm Endau Analytics originally told BBC.

Flying high: future targets and hurdles

Guiding the flight path: navigating complex technical uncertainties

Initially, there were high hopes for the ability of COMAC to quickly replicate the technological quality standards found among Western manufacturers like Boeing and Airbus. Airbus’ chief strategist Marwan Lahoud had even speculated that the C919 would emerge as a competitor by 2020. Ambitions for the C919 were strong with COMAC estimating to be able to produce and sell up to 2,300 C919 aircrafts.

Yet, the C919 encountered significant setbacks. The budget, originally 58 billion yuan (about $9.5 billion), exceeded $20 billion. Delayed due to technical and supply issues, its prototype, planned for flight in 2015, was rolled out on November 2, 2015, with the first flight delayed to 2017.

Once operational, the C919 faced criticisms, particularly for its cockpit noise interference. Its range and seating capacity also fell short of its Western counterparts impacting its efficiency and economic viability for airlines. Consequently, the C919 was deemed inferior to competitors. Analysts described it as an “overweight and stunningly obsolete” product with limited relevance outside China’s regional airline sector.

Safety first: meeting international standards

In terms of regulatory hurdles, obtaining licensees to fly in the air will be one if not the greatest achievement that a new aircraft manufacturer like COMAC needs to reach. Without those permissions, even the most promising aircraft remains effectively grounded.

COMAC’s first regulatory milestone was approval by Chinese aviation authorities. The C919, showcased in a 2020 airshow and undergoing certification tests, received certification from the Civil Aviation Administration of China in September 2022. So far, only China’s aviation regulator has certified COMAC C919 jets.

To gain significant global market presence, COMAC needs approvals from major regulators like the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA).On 4 January 2024, the Chinese Civil Aviation Administration of China expressed its intent to work with the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) to validate the C919’s airworthiness certificate for Europe. This is a further step from the signing in 2020 of a Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreement (BASA) between the EU and China to facilitate the reciprocal acceptance of findings of compliance and certificates issued by the respective Competent Authorities.

Engineering the future: what are the next technological breakthroughs?

To increase the future competitiveness of its currently commercialized models, COMAC will have to solve some technological challenges in its design and production phases which are leading to an unattractive production cost versus performance ratio.

A critical issue is the reliability and performance of COMAC-built engines. Currently, the C919 uses Leap-1C engines by CFM, a joint venture between GE Aerospace (U.S.) and Safran (France), with Honeywell (U.S.) as another key supplier. However, escalating U.S.-China tensions have made Western countries reconsider supplying advanced aerospace technology to China. Despite challenges, COMAC aims to develop indigenous engine technology.

Component quality and reliability, affected by a complex global supply chain, also challenge the C919. Foreign suppliers’ reluctance to provide advanced components due to IP infringement risks has led to the C919 using older technology than Boeing and Airbus planes.

Finally maintaining consistent quality across all parts and systems is vital for aircraft reliability and safety. Unlike Boeing and Airbus, COMAC lacks a widespread network of service and support facilities. Building a similar infrastructure and offering a range of C919 variants with global service is a necessary step that will take years.

Envisioning the future of Chinese aviation market

- China’s aviation market has grown rapidly, becoming the largest globally in terms of passenger numbers.

- COMAC, China’s state-owned aircraft manufacturer, has been focusing on reducing reliance on Western companies by developing domestic aircraft like the ARJ21 and C919.

- COMAC’s development of aircraft, particularly the C919, involved global partnerships but faced technical challenges in development and achieving international certifications.

- The COVID-19 pandemic impacted the aviation sector, affecting both Western manufacturers and COMAC, but recovery efforts in China have been robust.

- Despite some setbacks, Chinese ambitions to quickly integrate an indigenous manufacturer into the global aviation market, should make us think on the “when” rather than the “If” COMAC will be able to shift the aviation industry’s traditional duopoly.