In comparison to countries like the United States or France, China has recently entered the civil nuclear energy industry – its first plant became operational in 1994. But lately, China has been making up for lost time: its nuclear market is already one of the world’s biggest.

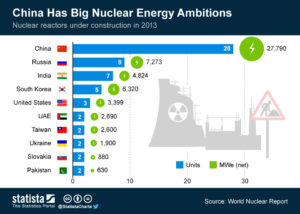

Today, twenty reactors are being built within China. This represents more than a third of all the reactors under construction around the world. They will complement the production generated by 36 nuclear reactors already in operation.

Source: Statista – World Nuclear Report

Despite its recent growth, we can expect more to come from China. During the last three years, the Chinese government has started to commercialise its national technology. Regarding security, economy, and geopolitics, the growing role of China as a nuclear force is likely to deeply modify the nuclear industry on a global scale.

Chinese nuclear energy: Substitution of nuclear energy to coal in order to support China’s economic growth

The first stake of China’s nuclear industry is economic: nuclear power must be able to answer the energy needs of China’s still dynamic economic development over the long term. Despite China’s GDP growth recently slowing down, China’s energy demand is still growing: energy consumption per person is on the rise and is expected to keep increasing until at least 2030.

In addition, in the coming years, “this demand should not exclusively come from the South Eastern coast anymore,”says Clément Mougenot, the Study Director at Daxue Consulting. According to the World Nuclear Association, around thirty zones in the mainland were already selected as locations to build a plant. Preliminary agreements were signed with the National Development and Reforms Commission (NDRC). Only the agreement from the State Council is left pending. Those zones are located in Sichuan (四川), Hunan (湖南), Jiangxi (江西) and Hubei (湖北), as well as in Liaoning (辽宁) (where several reactors are already operational) and Jilin (吉林) in the North.

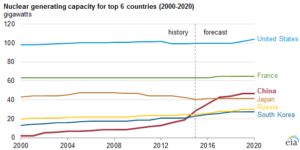

While the Chinese government is committed to a reduction in coal use, only nuclear power has the capability to furnish energy in a constant and reliable manner for China’s development needs. This is why the State Council Affairs revived several projects of power plants in the spring of 2015 after a four-year period of slowdown related to the Fukushima disaster. In 2030, nuclear power is expected to contribute between 8 % and 10 % of China’s energy use, whereas it contributed only 2% in 2012, remarked Xu Yuming, vice chairman of the Chinese Nuclear Energy Association to the China Daily.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

Exporting China’s nuclear technology in order to receive international recognition

While consolidating its nuclear production on the national scale, China is looking at energy needs beyond its own borders. Indeed, the two second-generation reactors launched in 2015, the Hualong One 华龙一号核电 and the CAP 1400 were not only conceived to satisfy the Chinese markets’ needs. On the contrary, they were designed to set an international standard, and thus provide recognition to China as a country with the know-how in the nuclear industry on a global stage. Economic stakes apply here once again: according to L’Opinion, building a power plant is as profitable as exporting 300.000 cars.

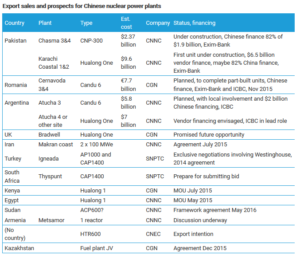

Given that China’s new reactors have not passed all the security tests yet (as tested by the European Union), the Chinese government has developed a key strategy to meet its mid-range goals. This consists of participating in projects that use foreign reactors but are supported by Chinese financial resources, expertise, and building services. Thanks to their financial power, China’s three biggest State nuclear companies (China General Nuclear CGN 中国广核集团, China National Nuclear Corporation CNNC 中国核工业集团公司, and State Power Investment Cooperation SPIC 国家电力投资集团) position themselves as the ‘saviour’ for international projects lacking funds.

This is how China participated in the construction of new reactors in Argentina (2014) and Romania (2015). The strategy is working since the CNNC was able to propose its Hualong One for one of the two new Argentinian reactors. In the United Kingdom, CGN will work on an EDF reactor in Hinkley Point, but it is waiting for approbation for another Hualong in Bradwell. Other contracts have been signed or are being negotiated with Saudi Arabia, Iran, Pakistan, and Turkey.

Source: World Nuclear Association, October 2016

Some security issues remain to be solved

This acceleration of China’s role in the civil nuclear industry at the international level is also raising security questions. Regulations for nuclear energy differ from State to State and countries that have little experience in nuclear energy have the potential to become China’s newest customers. For Jost Wübbeke, a China specialist interviewed by The Diplomat, this means that regulation framing nuclear projects in those countries may still be too young and loose to clearly assess their implications regarding security. This very issue is also valid for China itself, where security standards are high, but supervision is sometimes failing. However, the Chinese government wants to reassure both the international community and its own population about the quality of its technology: in April of 2016, China’s authorities unveiled a draft law on nuclear security.

Finally, China exports a share of its reactors to countries, such as Pakistan, which did not ratify the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapon. This raises questions and concerns among the members of the Nuclear Supplier Group, consisting of the World’s biggest nuclear power providers like France, Canada and Russia.