The Chinese working class is over five times bigger than the middle class. Businesses would be wise to pay more attention to them.

Everyone is talking about China’s middle class, but no surprises here. Estimates at the lower end of the spectrum total the Chinese middle-class to 110 million people (total workforce is 770 million). This is bigger than even the United States’ 92 million strong middle class and makes the spending habits of the Chinese middle class a force to be reckoned with–both in the Chinese and global economy. Numerous articles outline the growth – or stagnation as of late – of the luxury goods market, dotted with images of the Chinese middle class clutching Louis Vuitton handbags. Other reports discuss the rise of the sportswear market complete with interviews outlining how comfortable and fashionable Adidas and Nike sportswear is. But the middle-class forms just one narrow 11% slice of the Chinese population. Away from the buzz surrounding the spending habits of the middle-class is 623 million people of the Chinese working class.

This workforce was the primary driving force behind the double-digit GDP growth and the rise of China as a world superpower, not only producing products but also the crops that fuelled the masses of workers. Despite their integral importance in China’s growth little attention is focused on this group.

More Attention Should Be Paid to the Chinese working class

China currently holds the largest fraction of the world’s wealth at 16%, and it is no secret Chinese people are becoming more wealthy. This wealth rise will not be limited to the middle and upper echelons of the society but many of the Chinese working class should also see an increase in their wealth. These future urban and rural masses-come-consumers will bring their way of life to the market and understanding them should prove to be important.

For now, these people may not be buying designer handbags, sportswear, new cars, or health products, but in the future, these people and their children may become part of the middle-class, especially as wealth in the masses is predicted to rise significantly as soon as 2020.

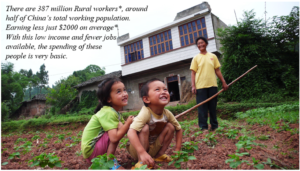

Photo and data from Doug Saunders

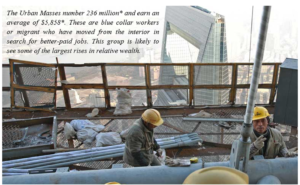

Photo and data from Chicago Tribune

Origins of the Chinese working class

Both of these groups have been shaped over 30 years since Deng Xiaoping first implemented economic reform policies. Over this time China has gradually transitioned away from a centrally planned production economy to a market economy (but retaining a focus on production). The transition starting in the late 1970s involved the decollectivization of agriculture, opening the economy to foreign investment and allowing entrepreneurship, followed by the privatization of many state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

Before Deng’s reforms workers were employed for life, factories could not dismiss them easily, and workers could not resign or transfer positions without the permission of a committee. This has flipped over and SOEs can now dismiss and recruit new workers with relative ease. This type of HR management style facilitates producing a profit which is the main goal of a company in a market economy. While this gives greater mobility to workers, it comes at the cost of an almost-guaranteed life-long employment and the loss of full social benefits that comes with their job. Although reforms have helped China realize a phenomenal increase in wealth and hundreds of millions have been brought out of poverty over the last 30 years, the wealth seen by large Chinese companies has not been felt by its workers to a significant degree.

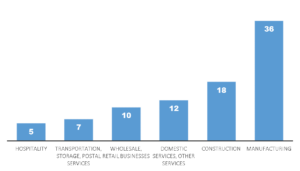

Employment Sectors for the Urban Masses

Most Urban Masses (formed by a mix of local blue-collar and migrant works) work in the manufacturing and construction sectors. The scale of workers in these two fields is no coincidence. Workers, and specifically migrant workers, are the main source of cheap labour for China’s factories and were largely responsible for China’s prosperous growth. Large numbers of construction workers were then required to build the cities that were needed as a result of economic growth. Other major sectors include retail as well as a mixture of various areas of work that fall under the ‘other’ category.

Data from Centre on U.S.-China Relations

The Awkward Existence of the Migrant Worker

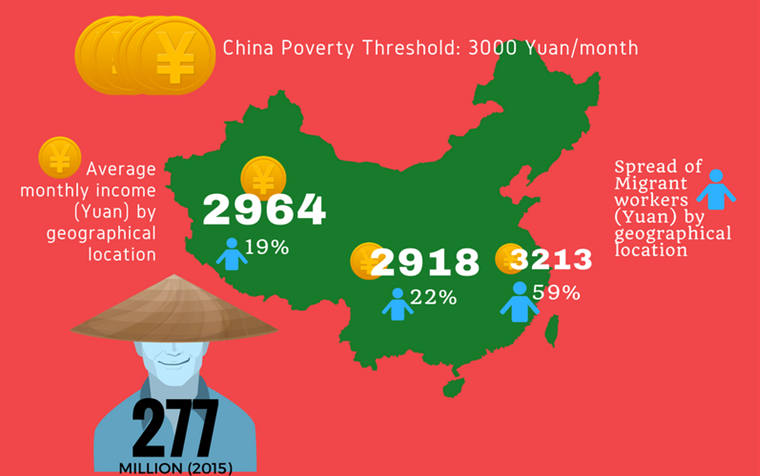

As for the rural Chinese working class population, many work in blue collar jobs in rural towns, or in agriculture, but a significant portion of the rural masses also become migrant workers drawn by a higher income of working in or near the cities. There are around 277 million of these migrant workers who come from China’s interior to urban areas concentrated in the east.

Many big SOEs focus on recruiting these migrant workers because are cheap labour who have incomes below the poverty line of 3000 Yuan/month back home in their rural areas. As China has minimum wages set significantly below the poverty line (as low as 2030 Yuan/month even in developed cities), companies need only pay workers a small magnitude above the average levels of incomes in rural areas to incentivise them. This explains the higher concentration of migrants on the east coast where China’s most developed, tier 1 cities are located.

Data from People’s Daily Online and Xinhua News Agency

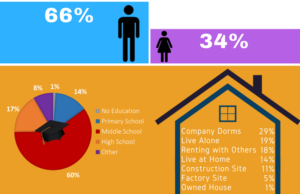

These migrants are composed of mostly men and are not educated past middle school level. Their lack of higher education means options are limited. Together with their labour being seen as a low price, profit maximizing commodity by employers this typically leads to workers generally lacking bargaining power and rights, and many live on company sites. These factors are probably some of the main contributors to poor working conditions with many working class migrants face which has been the focus of controversy recently.

The stigma attached to migrant workers as low skilled, low educated peasants or 农民 Nongmin means this group tends to be highly marginalized by Chinese society, despite being indispensable and accounting for half the country’s GDP. These workers face other problems other than a stigma. They cannot legally register in the cities they move to and so cannot to enjoy the social benefits that come with urban residency. Back home they are also unable to sell the land they own. Their situation is a double edged sword, despite working in the city they are not urban residents, and despite leaving the countryside they are seen as 农民 Nongmin.

Problems Faced by Migrant Workers

What can Businesses do to Anticipate the Partial Rise of the Working Class?

The hundreds of millions working class are forced to save money due to lack of access to education and other services. This is a restraint against the much-desired shift to consumerism. Ensuring these people have better access to services and safety nets is in the economic interests of China. As the shift to consumerism continues, this huge pool of the masses can act as a major catalyst for the Chinese economy as they did in the production based economy.

With them, they will bring their mindsets, likes, dislikes, cultures, and ways of doing things developed from their traditional ways of life.

To prepare for these consumers, businesses can look to the past for answers. Not so long ago Chinese consumers at all levels were too new to the market and took a pragmatic attitude to buying products. However, around six years ago, products and brands which consumers could form emotional ties started to perform better as consumers matured. This same behavior may be expected by the rising masses. However, these people have lived their lives budgeting frugally and spend on all but the essentials and they may require more time than the first wave of Chinese consumers and mirror the behavior of the older Chinese generation.

A further approach can be the implementation of a two-pronged strategy. In order to target both value and more wealthy customers, some companies provide value products (particularly focusing in lower tier cities) while simultaneously providing a more premium offering suited to middle-class consumers in higher tier cities. This would allow for consumers emerging from the working class to be targeted in addition to middle-class groups of consumers.

Also see our services: Focus Group in China, Naming in China.