After seven years of negotiations and serious concessions on both sides, the European Commission and the Chinese government finally reached an agreement on the European Union (EU)-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI). This investment deal serves to re-balance investment relations by allowing each party more access to each other’s market. As such, its successful implementation can and will significantly affect European businesses wanting to invest in the rapidly growing Chinese market and solidify a structured long-term Sino-EU economic dialogue.

How the EU views CAI

Overall, the EU views the agreement mainly as a business opportunity – a chance to increase market access, level the playing field, improve dispute settlement processes, and incorporate sustainability into the Sino-EU relationship. Over the past two decades, EU foreign direct investment stocks in China have outweighed Chinese investment stocks in the EU. Nevertheless, this trend has slowly been reversing and, in 2015, China became a net direct investor in the EU for the first time, with roughly €6.3 billion in FDI as opposed to the European €6 billion.

The EU attributes the increase in Chinese FDI, in part, to unfair practices (e.g. forced technology transfers, or disproportionate subsidies especially to state-owned enterprises) and its openness to foreign investments vis à vis a relatively closed Chinese market. The CAI should now mitigate these concerns through eliminating quantitative restrictions, equity caps, or joint venture requirements in many sectors; establishing transparency on subsidies, and SOE conduct, as well as limiting forced technology transfers.

How China views CAI

The Chinese government, whilst stressing its mutually beneficial nature, sees the CAI as an opportunity to improve its business environment through fair competition rules, and increased investment opportunities. Indeed, Chinese investment is increasingly facing opposition in Europe over national security concerns, particularly in high-tech sectors. The CAI could ease this opposition, especially if the real underlying reasons are concerns over unfair competition. Yet, China’s advantages extend beyond a business perspective. Geopolitically, it is an opportunity to deepen EU-China relations whilst sidelining the United States. After all, the agreement was reached just weeks before the Biden administration – which is particularly interested in restoring the transatlantic relationship – took office.

Yet, as in any agreement, one party’s advantage is to the other’s detriment. Western critics argue that, in this case, China has the upper hand. Indeed, some postulate that the EU has suffered a major geopolitical loss and violated “Western solidarity” by moving ahead on the agreement despite US opposition. Others argue that the agreement only really benefits the EU through opening China’s automotive and financial sectors, whilst other deliverables are too vaguely formulated that they may just be empty promises. In China, on the other hand, fears exist that the agreement could result in a sudden influx of German automotives that slow the country’s rapidly developing automotive industry.

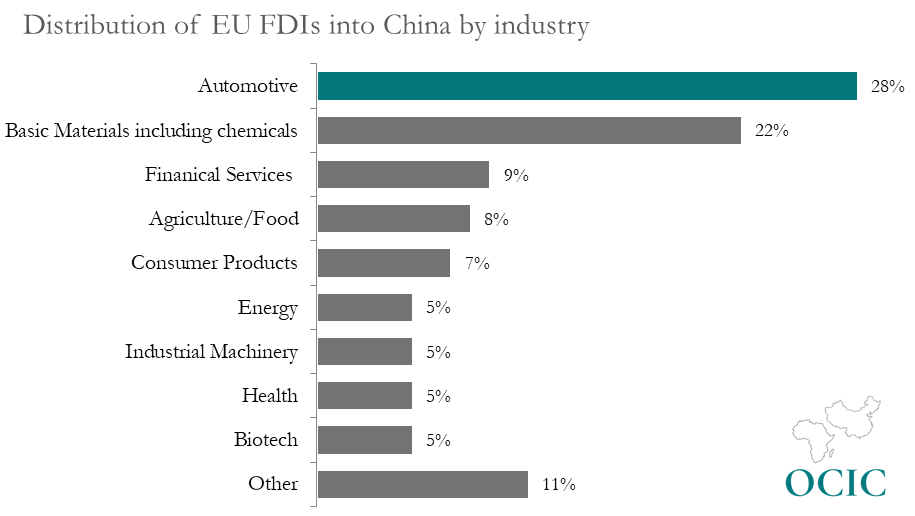

Data source: EU Commission: EU FDI into China is concentrated in the automotive industry

These fears, particularly on the Chinese side, are not completely unwarranted. After all, despite being limited by widespread joint-venture requirements, European investment in China is generally strategic, implying an inherent long-term focus. This matters because, in an attempt to rebalance market access asymmetries, as a part of the CAI, China made commitments that went beyond the scope and speed of its domestic liberalization program– thereby paving the way for increased EU investment in key sectors.

As mentioned, the strongest impact will most likely be felt in the automotive sector which currently accounts for 28% of total European FDI in China. While other areas of investment have been rather volatile, automotive investment has been a steady leader in EU FDI for the last five years. This is hardly surprising, considering that China has become a world leader in the automotive industry, particularly in the field of New Energy Vehicles (NEV). Indeed, McKinsey found that China’s NEV market accounts for roughly half of the global market, allowing it to dictate major industry trends. As a result, European companies have moved large R&D capacities for NEV technologies to China and many major European car manufacturers have partnerships with Chinese technology companies on autonomous driving, as missing out would be fatal.

Nevertheless, existing joint-venture requirements and targeted subsidies to Chinese firms continue to kneecap European firms in their competitive standing in the Chinese market. European car manufacturers currently need to enter joint-ventures with Chinese counterparts, in which the foreign partner is required to hold less than a 50% stake. As a result, the majority of European automotive FDI comes with a non-controlling stake. The CAI will now change these limitations, allowing for European majority stakes, and lifting joint venture requirements altogether. In addition, the agreement foresees a suspension of subsidies and more transparent subsidy control mechanisms. Without those restrictions, the situation looks truly different for European car manufacturers.

Potential impact of the CAI

As the CAI seeks to materialize the market liberalization EU firms have yearned for since China’s reform and opening up, the million yuan question arises: what exactly does the CAI mean for the future of EU companies in China? In recent years, Beijing has taken it upon itself to begin loosening many restrictions deemed disadvantageous to foreign firms, approving a group of companies to set up wholly owned foreign enterprises or increase their market share in joint ventures. These cases offer us a brief glimpse into the broad possibilities of what is in store for all EU agencies post-CAI, specifically in the automotive and financial services sectors.

How will CAI look like for Auto companies? Tesla vs. BMW

When Tesla first dove into the Chinese market in 2013, its entrance without a domestic joint venture partner sent shockwaves through the international auto industry. In what can be judged as a move to open up further, Beijing made an exception to its non-majority stake rules and granted Tesla access to construct a wholly owned foreign car plant in China. This move has provided the company a reprise from tariffs instigated by external trade wars and precipitously lowered shipping costs. To date, Tesla is the leader of the Chinese EV market, claiming a 5th of all electric vehicle sales in the country.

Through the direct entrance into the Chinese market with a Wholly foreign-owned Enterprise (WFOE), Tesla has been able to circumnavigate many of the obstacles other foreign auto firms have faced when entering through joint ventures. Without the impediment of managerial control issues, the firm has been able to use its authority to boost overall margins and reap major returns in the world’s largest auto market.

In light of the CAI, we can also turn to BMW as an example of an alternative model to JV opening up. In 2018, Beijing announced a reform granting auto firms the ability to own a higher stake in Chinese ventures than the previous 50% permitted. BMW was the first company to pounce on this opportunity, immediately engaging in dialogue with its JV partner, Brilliance China Automotive, to increase its stake from 50% to 75%, according to BMW Group. The deal was ultimately brought to fruition, albeit for a pretty penny: BMW was required to pay 3.6 billion euros by the next decade to expand production capacity at their two Shenyang plants. Following the agreement, BMW CFO Nicolas Peter expressed satisfaction with their new controlling majority, but explicitly stated that the company has no plans to expand the stake further.

The BMW case ultimately signals that it may be an onerous and expensive process for auto brands that have their feet already dipped in China to transition from 50-50 JVs to a majority stake position or WFOE. Although this may be the case, by obtaining greater control of their Chinese JVs, global auto firms will be able to realize substantial profit gains and mitigate managerial disputes that undermine strategy. With the implementation of the CAI, automakers and firms in other industries alike will be granted the opportunity to decide for themselves on a Sino-structure, dispelling a 50-50 JV deal as the sine qua non of doing business in China.

In sum, then, these case studies demonstrate the immense implications the CAI might have, both for European firms wanting to invest in China, and Chinese firms fearing increased European competition. If fully ratified by both sides, the CAI will become a milestone towards a more structured and deeper Sino-EU economic relationship.

Authors: Michael Schroeder, Elise Bukowski and Philipp

Hackel from the Oxford China International Consultancy

Learn something new? Stay updated on the Chinese market by following our WeChat, scan the QR code below, or subscribe to our newsletter

Learn more about the M&A market in China

Listen to over 100 China entrepreneur stories on China Paradigms, the China business podcast

Listen to China Paradigm on Apple Podcast