The bike-sharing market in China has a broad customer base, a verifiable business model, and good operating cash flow. It is one of the most popular investment areas in the primary market in the past few years. The rapid influx of capital has accelerated the evolution of the industry and has directly increased the competition.

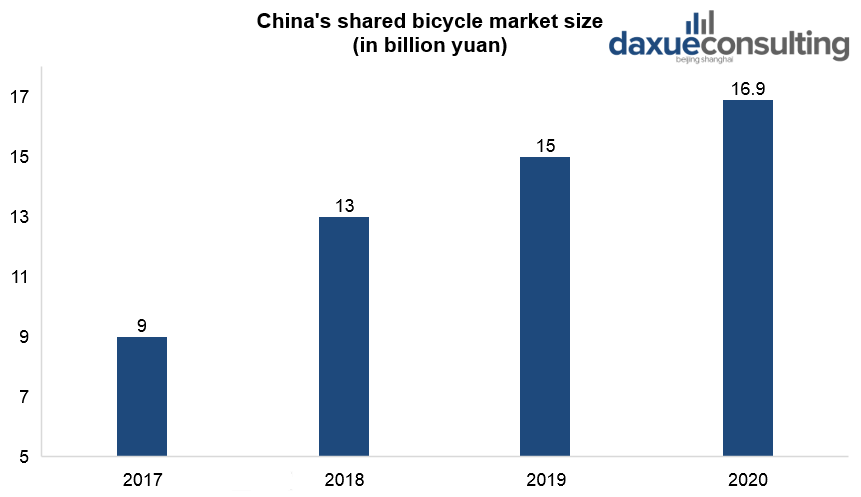

[Data Source: Zhiyan, ‘China’s shared bicycle market size’]

In 2018, the bike-sharing market in China reached 13 billion yuan, a 73% increase in quarter on quarter. It happened mainly due to the market expansion in second-tier and third-tier cities. Forecast shows that the size of China’s shared bicycle market will reach 17 billion yuan in 2020. However, while the bike sharing market was rapidly growing, one of the top bike-sharing brands, Ofo, made headlines with financial problems.

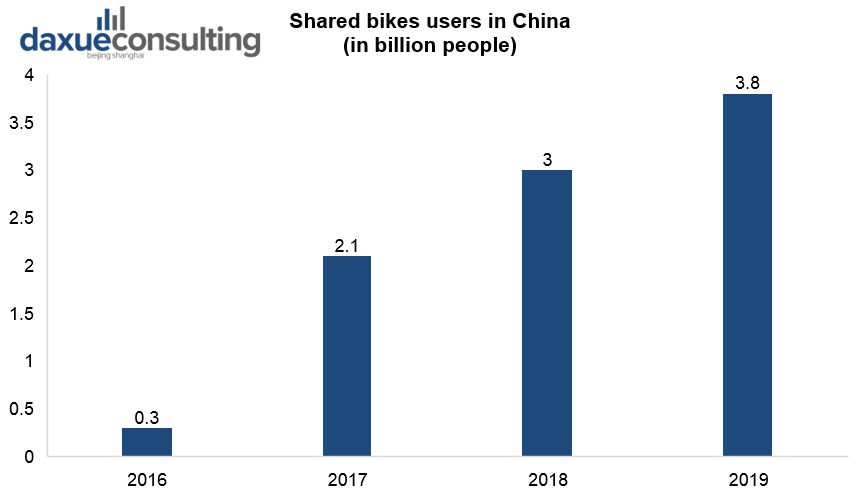

The number of shared bicycles users is increasing in China

The scale of shared bicycles has expanded rapidly in China, with over 300 million registered users in 2019. As of the end of August 2019, there were 19.5 million rental bicycles in China, covering 360 cities across the country. The average daily order number reaches 47 million.

[Data Source: China Bicycle Industry Conference, ‘Shared bikes users in China’]

People mainly use shared bicycles for travel needs at a distance of less than 3 kilometers. In 2018, more than half of users used shared bicycles more than 5 times a week, mainly for short travels. The demand for cycling is higher in the first-tier cities. In 2018 demand in the four first-tier cities was between 57% and 66%.

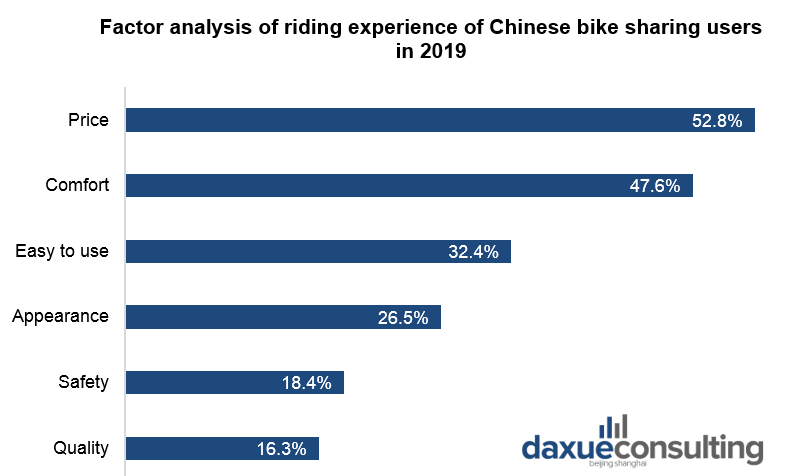

According to statistics, the cost of shared bicycle has become the biggest factor affecting user experience, accounting for 52.8%. Cycling comfort ranks second, accounting for 47.6%.

[Data Source: Prospective Industry Research Institute, ‘Factor analysis of riding experience of Chinese bike sharing users in 2019’]

Mobike and Ofo: the key competitors in the Chinese bike-sharing market

Mobike backed by Tencent

The orange shared bike, Mobike, was one of the first pioneer in the bike-haring market in China. It is a startup financed by Chinese tech giant Tencent and Chinese investment firms. Mobike is a high-end branding segment with flashy orange wheels, incorporated satellite navigation.

Ofo: backed by Didi

The drive APP Didi is the main investor in Ofo company. Ofo in China is focusing on students with their yellow bikes that cost around 250 CNY. They have a sharing economy model. The specific feature of Ofo in China is that people can share their own bike. They can offer its services from one to three years and the company is going to repaint it and put an Ofo lock on them.

Breakdown of the shared bike market in China

For over a dozen years, racks of publicly shared bicycles have been a common sight in China’s megacities, but only recently have urbanites developed a taste for riding them. While city governments often set up their own public bike-sharing programs, these bicycles belong to two innovative start-ups, Mobike (摩拜单车), launched in April 2016, and Ofo (共享单车), which was launched five months later. Both aim to control a very promising market, that promising that bike sharing has already more than doubled the usage of bicycles in China. In doing so, the two start-ups have grown rapidly since their inception, with Mobike accumulating a total of 3.65 million bicycles, and Ofo building a fleet of 2.5 million. Having devised a unique business model in China, Ofo’s next move is to set up shop in Silicon Valley. Now both Mobike and Ofo turn towards the rest of the world.

The two leading bike sharing companies Mobike and Ofo are aware of how convenient bikes can be. Taking the example of Beijing, 93% of travels less than 5km are quicker done by bike and public transport than with the car. Drawing on this convenience aspect, their business models rely on bikes that can be ridden and left anywhere in the city (or a defined area) thanks to a free, easy-to-use application and an efficient geo-localization system. This kind of bike sharing service model eliminates the need for traditional bike terminals and stations. China, namely, may have the largest bike sharing system in the world but it posed serious questions of profitability for the cities that host bike-sharing systems themselves. Ofo’s and Mobike’s model is, therefore, a leading business model in China, especially with regard to cost-and time-saving.

Rental bicycles languished for a decade without attracting the public

Victims of severe air pollution and traffic congestion, Chinese cities adopted bike sharing programs en masse beginning in 2008. According to The Earth Policy Institute, seventeen of the top twenty cities in the world by bike fleet size are in China. The first is Hangzhou (杭州), a metropolis of nine million inhabitants west of Shanghai, where residents share and ride a stupefying 86,800 bikes, according to different local sources. Shanghai (80,000 units) and Beijing (86,000 units) also rank high on the list.

Ubiquitous though they may be, many public bike-sharing systems simply go unused. One of the reasons for the failure of bike sharing in such cities, despite being a cheaper option than Ofo and Mobike (starting from 0.5 to 1 RMB per hour, compared to about 2 RMB for Mobike and Ofo) is the price and complexity of the deposit system. To use public bicycles, users must pay a minimum deposit of 200 RMB, plus a prepaid card ranging from 100 to 400 RMB, depending on the payment method used. In addition, the need to take and return bikes to stations as well as the lack of stations in some cities limited the development of bike sharing. Even though residents of megacities are more sensitive to air quality and mobility issues, bike sharing systems were not able to fulfill the government’s expectation of success.

Photo credit: Daxue Consulting.

A new system solving the “last kilometer” issue

The ride-sharing model adopted by municipal programs does not address the “last kilometer” issue, which refers to the distance between the subway or bus stop and a passenger’s final destination. Ofo and Mobike answer precisely this need by enabling users to take and leave their bikes wherever is convenient. The user looks for nearby bikes or geo-localizes them with his smartphone, then scans the QR code of the bike he has selected. For Mobike, the QR code instantly unlocks the bike. Ofo users must additionally enter a four-number code sent to their phones via the app to unlock the bicycle.

The applications developed by the two companies accept payments via WeChat or Alipay, the two most popular digital wallet platforms in China. Mobike offers four models: Mobike Classic, MobikeLite and two ultralight models to provide a larger range of choices for its clients. Ofo, meanwhile, wishes to develop the “城市共享计划” plan, which gives private riders the option to rent their personal bicycle to other Ofo users in exchange for a free subscription to the service, in addition to its three current models: Ofo 3.0, Ofo 3.1 and Ofo Curve.

An increasingly competitive market attracts investors

Owing to their parallel development of a leading business model in China, the two start-ups are now competitors. Ofo, founded in 2014 by four Beijing University students, initially targeted students and professors by installing their iconic cheap yellow bikes on 200 university campuses in 19 Chinese cities. Now present in 44 Chinese cities, with 3.69 million weekly users and an average of 500 000 rides per day, the start-up turns to face overseas markets.

The brand, nicknamed by the Chinese “小黄车” (“little yellow bike”) has offered its bicycles on the campuses of Singapore universities since February 2017. But Ofo’s ambitions went further. On April 22nd, 2017, the company launched a test run in Austin, Texas during the South by Southwest Festival (SXSW), before opening its service to the students of Harvard University. This launch marks the first step of Ofo’s international expansion plan, which delineates a vision to reach ten American cities during 2017 and enter the European market beginning with London.

Tense competition between Ofo and Mobike

Ofo would thus play on Mobike’s field. Mobike pioneered the concept in Shanghai in April. Now, with a penetration rate of 13.9% according to iResearch, the market leader is currently present in more than 50 cities and boasts 7.69 million users per week. The brand’s basic models, Mobike Classic and MobikeLite (featuring silver red wheels in Beijing and orange wheels in Shanghai) target middle and upper-class consumers. For instance, while Ofo only asks new users for a deposit of 99 RMB to register with the service, a Mobike account costs 299 RMB up-front. However, the service price is equivalent to 1 RMB for a half hour ride and 0.5 RMB with MobikeLite.

In China, Ofo kicked into high gear. Since the beginning of 2017, the start-up pursued an aggressive expansion plan foreseeing the addition of more than 10,000 bikes in eleven cities over a period of ten days. Moreover, much alike its challenger, Mobike started an international expansion strategy. According to the Head of International Expansion at Mobike, Florian Bohnert, the company started operating in Singapore on March, 21st this year, where Mobike dropped their bikes on university campuses or in front of shopping malls, for instance.

Will the two shared bike companies’ international expansion last long?

This should be only the start of a broad international expansion as the founders of Mobike believe in global demand since day one. Future target markets, so Bohnert, will be areas where pollution is a problem and where the government pushes a “green lifestyle” like in Singapore. However, this not only includes expanding in different Asian markets but to “different continents”.

The dazzling success of Mobike, pioneer of the effective ride-sharing business model in China, attracted a wave of new entrants on the sharing bike market. Photo credit: Daxue Consulting.

Investments in Ofo and Mobike

In the space of a few months, the bicycle sharing market has become one of the most popular sectors in China, attracting the world’s largest investment funds. After receiving several hundred million dollars from four funds, and earning the support of Sequoia Capital in October 2016, Wang Xiaofeng (王晓峰), the former manager of Uber Shanghai and founder of Mobike, received recently more than one million dollars from Temasek (淡马锡), Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund, in February. Russian investment company Digital Sky Technology (DST) invested in Ofo in March, after Ofo had convinced five Chinese funds to invest. Recently, this promising niche has also attracted the tech giants.

While the mobile maker Xiaomi (小米) invested 130 million dollars in Ofo last October, competing Mobike received 200 million dollars in January 2017 from Foxconn (富士康), Apple’s main supplier, and Tencent (腾讯) the Chinese web giant. Nevertheless, Ofo had not been left behind. The yellow bike startup also received a first payment of 130 million dollars in September 2016, and a second payment of 450 million dollars from DidiChuxing (滴滴出行), the car transportation mobile app, in March 2017. Ofo announced its new fundraiser with Ant Financial (蚂蚁金服), the subsidiary of the Chinese online giant Alibaba (阿里巴巴) this April. However, the amount of funds transacted in this agreement was not disclosed. During a courtesy visit to Beijing this last March, Ofo also succeeded to grab the attention of Tim Cook, Apple’s CEO.

Can the model of Mobike and Ofo be exported?

Based on the results of the business model in China, will we see Mobike and Ofo’s orange and yellow bikes navigate the streets of foreign cities?

Mobike and Ofo attract users and cities in charge of bike sharing systems: the elimination of stations to take and leave bikes improves user experience by removing one of the main constraints of typical bike sharing systems.

In the other hand, constructing and maintaining these stations is costly for both the companies that own them and the cities that operate them. The terminals and stations created by JC Decaux, for instance, require a particularly high level of civil engineering work. Removing them would likely lead to significant economies. Compared to this model, the system developed by the two new Chinese bike sharing players merely includes an application to geo-localize bikes, unlock them; and third-party applications handle the transaction – no more infrastructure.

Financial profitability issues for this business model in China

Ofo and Mobike, like JC Decaux and Smoove (a French start-up that developed a connected bike sharing system) and most public-private bike sharing programs, face the same issue of profitability: users’ contribution to program funding is too small to make facility setting (when they apply for membership) and maintenance profitable. In Marseille, for instance, the operating cost of one single bike is estimated at 3,267 euros, according to consulting firm Mobiped. Helsinki went bankrupt and had to close the stations set up by JC Decaux. The group took seven years altogether to turn a profit on this activity, despite its innovative financing model based on the acquisition of advertising spaces in cities in exchange for bike sharing stations.

In China, such programs are integrally funded by the State. According to Icebike.com, in Shanghai, the fourth most shared bike fleet worldwide, the Forever Bikes (永久), which owns 200,00 units, just reached the balance point. Even though Ofo and Mobike only have to handle their fleet, neither company is in the black, and given the one or two RMB price per ride, this may not happen soon. In November 2016, the founder of Mobike announced: “it’s too soon to think about making a profit.”

Many new competitors enter the market

In China, more and more new entrants want to penetrate this juicy market. No less than seven new bike sharing companies, including U-Bicycle (优拜单车), Xiaoming (小鸣单车), Blue Gogo (小蓝单车) and Qibei (骑呗单车) claim to compete with Mobike and Ofo. Launched in 2010, Youon (永安行) is a serious competitor for the two market leaders. The company, soon to issue its stock publicly, is supported by the Chinese government. It generated 62.08% of its turnover from 2014 to 2016 through Business-to-Government operations, while its revenue from bike sharing represented only 0.05% of the total. Should Ofo and Mobike start selling their bikes to the government?

Chinese smartphones host an ever-increasing number of mobile bike sharing applications. Source: iiMedia.

If the Chinese business model for bike sharing were exported to France for example, would users willingly pay more for the services offered by Ofo and Mobike? In Paris, a Vélib subscription costs between 29 and 39 Euros per year, and daily riders may renew their subscriptions almost for free. Moreover, tariffs proposed by the two Chinese enterprises, adjusted to the cost of living in Paris, would probably be judged too expensive by consumers, even if prices remained lower than public transportation tickets. Again, profitability issues would likely surface.

Vandalism: another obstacle for the growth of bike sharing

The unique business model developed by Ofo and Mobike is unlikely to flourish in cities where the risk of vandalism and larceny is high. In Paris, whose bike fleet of 16,200 units is the world’s fifth largest, one thousand bikes are stolen each year. Last year, though 91% of theft cases were solved, 27% of the bikes recovered were unusable.

Some of the bikes that circulate through Chinese megacities are also damaged or stolen. Hangzhou’s own fleet is victim to casual vandalism, despite its featuring hardier bikes and means of anchoring cycles to the terminal. Therefore, it would be ill-advised to export this bike sharing model to cities like Paris before improving security on the ground in China.

A recent report published by Tencent (腾讯) on the future of bike sharing companies and their users (« 解读摩拜ofo们的用户与未来») shows that 39.3% of Ofo’s first cohort of users reported failure or malfunction through the app, compared to just 26.2% of Mobike’s users. Two factors explain the high rate of malfunction for bikes operated by Ofo (Ofo 3.0 and 3.1). On one hand, the quality of Ofo’s bikes first generation is inferior, and on the other hand, a software bug allowed users to ride for free, causing the risk of vandalism to rise.

One maintenance employees in charge of Ofo bikes in Beijing on Qingnian Street (青年路) testified in an article published by the Chinese newspaper VOC (华声在线) that nearly 1,000 of the 10,000 bikes in the area were damaged within a month. To solve this quality issue, the brand launched a new, lighter model in March 2017. The upgraded bicycle was dubbed OfoCurve, and included a new electronic lock and basket.

Ofo has found its muse in the Chinese superstar Luhan ( 鹿晗) for its recent advertising campaign accentuating the lightness of its third bike model, Ofo Curve. Source: Ofo.

These acts of vandalism even spawned “bicycle hunters” (单车猎人): paid persons who repaint license plates and to report the numbers of bicycles out of service or damaged.

Illegal parking can severely damage bikes. Source: Ofo-bankrupt.com

On April 27th, 2017, ten Chinese bike sharing companies, including Ofo and Mobike, signed an agreement with the National Development and Reform Commission (国家发改委) and the National Information Center (国家信息中心) authorizing the sharing of user data. This agreement would reduce vandalism and illegal parking. The ten companies will be able to share credit data between users and access information in government databases on the Credit China website. In the near future, users with poor credit will be face limitations in terms of how often they may rent bicycles, while those with better credit will enjoy more benefits.

A collaborative economy context

Despite the issues encountered by this business model in China, the enthusiasm for Ofo and Mobike’s services amongst consumers reveals a real demand for sharing and renting in China, as well as an underlying trend. In 2016, the collaborative economy in China surged, particularly in the urban transport sector. By collaborative economy, we mean two aspects: first, “sharing economies” like DidiChuxing where individuals rent-out own assets. Second, “on demand rentals” where Ofo or Mobike are perfect examples.

Meanwhile, other modes of transportation can be shared, too. Launched in April 2015 in Chongqing (重庆), a South-west city of China, the Dutch car sharing service Car2go (即行), launched by a subsidiary of the automaker Daimler, has accrued more than 250,000 users. Within two years, the start-up has extended its service to six Chinese cities. Like Car2go, Togo (途歌), launched in 2015 in Beijing, has won more than 100,000 members in 2016 and raised 40 million RMB (5.7 million Euros) in early 2017. SAIC Motor (上汽集团), China’s largest carmaker launched its bike sharing service, EVcard, in 2015. This serious competitor to Togo boasts 1,600 electric car sharing stations, mostly located in Shanghai’s Jiading District (嘉定区).

Due to high prices and a slow pace of development, the car sharing market represents 0.5 and 1 million users while bike sharing has topped 20 million users, reports IResearch. The latest trend in shared urban mobility? Electric scooters. Innomake Technology (云造科技)), a young Chinese start-up from Hangzhou (杭州), holder of the smart bicycle brand UMA (云马), an acronym standing for Urban Mobile Actor, unveiled this concept in March 2017 in Guangzhou. While accident responsibility issues are not yet set, scooters are currently only available in enclosed spaces such as parks or universities.

After bikes and cars, here comes electric scooters sharing, the new Chinese UMA brand (云马) launched in Guangzhou. Source: 96u.com

The collaborative economy affect beyond

The collaborative economy is not limited to renting vehicles or apartments. Thanks to the two flagship mobile payment applications, WeChat Wallet and Alipay, the emergence of new business models in China is much faster than in other countries. The latest example is 魔力伞 (Molisan, meaning “magic umbrella”) a start-up from Guangzhou (广州). Since March 2017, citizens can rent umbrellas from a simple scan of QR code for 2 RMB a day (20 RMB of security deposit). Currently, 1000 rental umbrellas are available in six subway stations in Guangzhou. The concept has already attracted more than 4,000 users and Molisan plans to distribute 1 million umbrellas in Guangzhou before expanding into the city of Fuzhou (福州).

Sharing umbrellas in Guangzhou streets available via借借(borrow in Mandarin), a Chinese application for swap and share goods between private individuals.

Since April 2017, “猪了个球” (ZhuLeGeQiu, whose pronunciation in Mandarin is similar to ‘Rent a ball’) provide a basketball sharing service in Jiaxing (嘉兴).The service price for renting a basketball (stowed in a locker which is also rented) is equivalent with 1.9 RMB for a half hour (29 RMB of deposit) payable via the WeChat service account.

The company, which has already received the support of a Chinese investment fund, plans to expand in 23 Chinese cities to cover 80% of the stadiums in China.

Overall, driven by the Chinese interest for sharing and rental services, collaborative economy is expected to grow 40% annually until 2020, according to the Chinese government.

HOW TO DEVELOP YOUR BUSINESS MODEL IN CHINA

Listen to 100 China entrepreneur stories on China Paradigms, the China business podcast

Listen to China Paradigm on Apple Podcast