The year 2021 has been the turning point for China’s idol economy. After several years of booming growth, it fell into decline from July 2021 onwards. The “Operation Qinglang” (清朗运动, the operation to cleanse the entertainment industry) launched by the Cyberspace Administration of China in August dealt a huge blow to the idol economy. With the Chinese government tightening its policies on the entertainment industry, the idol economy in China is set to enter a cold winter for the near future, which warns brands to choose their partners carefully and to revamp their previous approach to idol promotion.

What caused the collapse of the idol economy in China?

The collapse of the idol economy did not happen overnight. Chinese netizens have expressed anger against the actions of idol fans (known as “stans”) over the past few years. The famous Chinese actor, Xiao Zhan and the “2·27 event” caused by his fan group is one of the most influential incidents triggering the collapse of China’s idol economy.

The “2·27 Event”

In typical Chinese fan culture, it’s considered the fans’ responsibility to defend the image of their idols. Fans would set up online organizations to “clean up” (净化) any negative comments about their idols by reporting or spamming the posts. In the “2·27 event”, a fanfiction published on Archieve of Our Own (AO3), an international fanwork website, was deemed by Xiao’s fans to be an insult to his image. In response, thousands of Xiao Zhan’s fans reported this site. Coupled with strict official control over foreign websites in China, this reporting action eventually led to the site being “walled off” and its mainland users no longer being able to log on.

This incident caused an outcry from AO3’s mainland users and resulted in a strong boycott for products endorsed by Xiao Zhan. Netizens, who accused Xiao Zhan as being “unworthy of his position” and “not being able to guide his fanbase appropriately”, created detailed lists of all the brands associated with Xiao to boycott them.

According to Jiemian News, the incident dealt a strong blow to both Xiao Zhan and his associated brand. Despite Xiao’s continued reign as the number one in terms of popularity on Weibo Idol Chart prior to the 227 incident, when the influence of fan culture went beyond its normal scope, the effect of idol economy turned out to be counterproductive for related brands.

Idols and their “stans”

Under an idol economy model, brands tend to target the crazier parts of fan bases. Each of whom, despite their small numbers, has a blazing willingness to buy. In fact, a 2019 AdMaster survey showed that 73% of Chinese fans are willing to spend money for their idol. The classic slogan of Xiao Zhan’s fans, “Buy One Bite Three” (买一咬三, if you can afford one, you have to bite the bullet and then buy three) is a manifestation of their fervent support for the idol economy.

Brands, therefore, exploited this mentality by tying their products to the “reputation” of their idols to incite irrational consumption. In the TV show Youth with You, fans were given voting rights to elect their favorite idol by buying milk drinks. Each carton of milk contained a “milk vote”. It drove fans to buy a huge amount of milk only for the virtual vote rights inside. They didn’t care about the quality, taste, or price of the product itself – in fact, a video of fans dumping milk down the drain has gone viral.

Chinese netizens were shocked and dismayed by this extremely wasteful behavior. The official media, People.cn, also criticised the act by name. The extreme behavior of the fans and the economy they support have been heavily criticized by ordinary consumers over the years.

Scandals and misbehaviors

The decisive factor that drove the decision to burst the bubble of the idol economy has been a series of scandals involving several top idols in 2021. The most shocking one was the rape scandal involving Chinese-Canadian rapper and actor Kris Wu. The former “top-streaming idol” (顶流) has long been a figurehead of the Chinese idol economy. In addition to his huge fan base, his look has always been appreciated by fashionistas and welcomed by young generations. Before the scandal broke, Kris Wu was the brand ambassador for several first-class luxury brands, such as Louis Vuitton, Bulgari and Burberry.

However, in July 2021, Wu was accused of forcing women to have non-consensual sex with him, some of whom being minors. This serious crime forced the brands to quickly terminate their relationship with Wu to minimise the negative impact of the scandal on them.

Immediately afterward, in August, another Chinese idol actor, Zhang Zhehan, was pictured in close association with a right-wing Japanese figure. Photos of him visiting several shrines and mimicking inappropriate hand gestures left netizens shocked: how could such a person become one of China’s most popular celebrities and endorse by so many brands? Like Kris Wu, the brands that worked with Zhang Zhehan immediately announced that it had terminated the star’s contract.

In addition to these two scandals, the negative press for Zheng Shuang, Zhao Wei and other celebrities continues to frustrate Chinese netizens and consumers. These scandals have worsened consumer distrust of idols, while allowing Chinese officials to step in to regulate the idol economy.

Operation Qinglang: The government’s regulation of China’s fan culture

The ongoing discontent with reckless fans and the idol economy in general have caused Chinese netizens to rebel against fan culture. In response to the internet’s outcry, Chinese officials decided to tackle the “fan culture” and started the “Qinglang Campaign” in August 2021.

The “Qinglang Campaign” is a comprehensive crackdown on “fan culture” in China. Firstly, Chinese officials have made it clear that they “do not support” irrational fan behaviour. This stern attitude required brands to take a careful look at their collaborations with idols in China. The traditional model of an idol economy, which relies on the purchasing power of fans, would clearly pose a great risk to brands.

In addition, several fan culture-related apps have been taken down or scrutinized. These apps mainly functioned as platforms for fans to “fundraise” or “vote”. In some cases, when some fans were not financially able to buy products endorsed by their idols independently, fan groups would call on them to put all their money into a fund on these platforms to raise money for the collective purchase. The Central Internet Information Office reported 39 small programs suspected of crowdfunding and attracting traffic had been intercepted and taken down in Qinglang Operation. The removal of these apps made the once-popular “fundraising” activities for idol economy almost impossible.

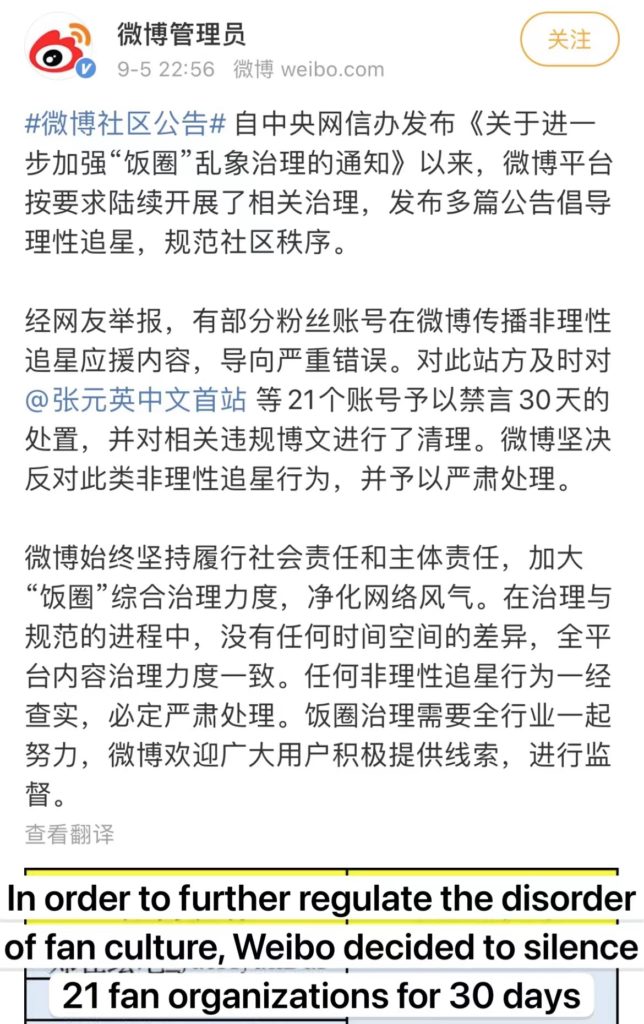

Finally, Chinese social media platforms also placed direct restrictions on many fan groups. The online fan groups of some well-known artists were banned on Weibo for a month. For this reason, almost all fan groups are now trying to find ways to evade the storm. They are changing the usernames of social accounts and calling on their followers to keep a low profile.

How Chinese fan culture is getting past Operation Qinglang

Operation Qinglang has dealt a huge blow to China’s fan culture, but the love and loyalty of fans to their idols does not seem to be so easily eroded. Under strict restrictions, fans are developing new ways to support their idols. To avoid censorship and accusation, fans are using the characters for “orange” (橘子, Juzi) emoji to refer to words such as “fundraising” (集资, Jizi) in their communications to disguise fundraising activities. Fans have only given up on publicly supporting their idols because of the strict official crackdown, their enthusiasm has not disappeared.

Also, not all idol endorsements have disappeared. While brands are now avoiding the hassles of the idol economy, many overseas brands are still able to use overseas artists to get around the official restrictions. Olens contact lenses, endorsed by the famous Kpop girl group Blackpink, are still giving away artist cards as part of their Double Eleven campaign to boost spending. Wang Jiaer, a famous Hong Kong rapper, has also launched collaborations with Armani perfumes, among others. The endorsement of idols is still happening, but brands are choosing to take a more subtle, safer approach to entice fans to buy.

What brands should know about the new direction of China’s idol economy

Faced with consumer discontent and strict official controls in China, brands should and are trying to find new ways to adapt to these changes in the Chinese market.

Choosing healthy endorsement mechanisms

Direct promotion approaches such as the ‘milk votes’ are no longer an option, and brands need to tap into the cultural value of idol endorsements. The collaboration between Oreo and Jay Chou is a good example of brand value and artist character and serves as a successful case of idol endorsement. At the same time, brands should also change their promotional approach and stop counting on fans to go on a consumption spree and instead look at long-term, healthy partnerships.

Choosing more wholesome artists and celebrities

To avoid the risks associated with the idol economy, brands should also expand their choice of endorsers. Artists who are widely recognized by the public are a good choice. At the same time, brands can also choose celebrities in e-sports or sports for endorsement. For example, RuiXing Coffee has established a partnership with Olympic champion Eileen Gu. These celebrities have the same influence as idols, but are usually tied to less scandal, making them a safe alternative for brands.

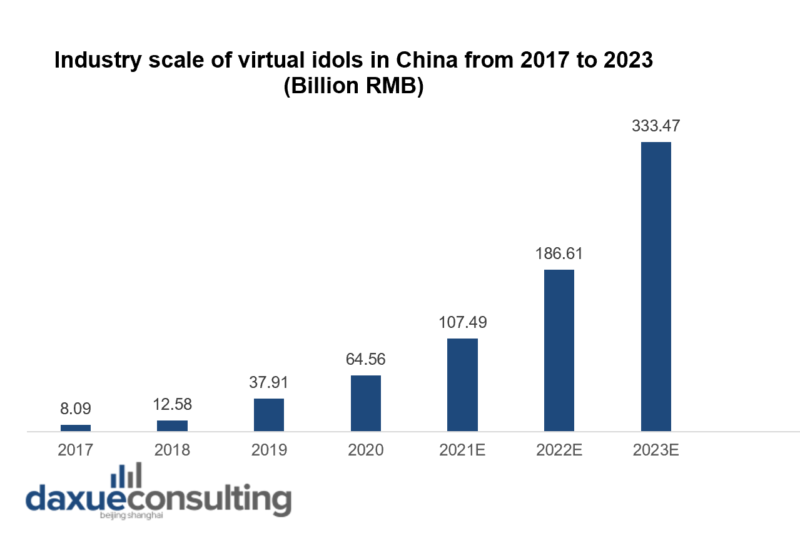

The development of the Metaverse

On October 31st, an account named “Liu Yexi” posted her first video in Douyin. With people’s curiosity towards metaverse and virtual idols, the debut video of Liu Yexi, this cosmetic celebrity, has harvested more than 3 million likes and more than 2 million fans in a week. In addition to this, virtual idols such as AYAYI are also actively involved in the promotion of the fashion and beauty industry. For brands, virtual idols have an appealing appearance while not being a risk for potential scandals, making them looking like promising alternatives for the future of the idol economy.

Key Takeaways surrounding the changes in the Chinese idol industry

- The behavior of reckless fans and the scandals surrounding the idols themselves have seriously undermined the idol economy.

- The Chinese government’s “Qinglang Operation” to crack down on fan culture has brought the idol economy to a turning point.

- The current stagnation of the idol economy does not mean that idols will disappear in China; fans still love their idols, it is just that extreme forms of fandom have been banned. There is still potential for fans to find new ways to support their idols when possible.

- For now, brands can consider collaborating with well-established idols and developing partnerships with virtual idols to hedge the risks of the idol economy.

Learn something new? Stay updated on the Chinese market by following our WeChat, scan the QR code below, or subscribe to our newsletter