On August 10, 2021, the Chinese State Regulation for Market Regulation (SAMR) launched a set of new provisions restricting excessive packaging of food and cosmetics (GB23350-202X) in China under the supervision of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. The new packaging regulation in China replaces the previous provisions defined in 2009 and is to be enforced by September 1, 2023. This buffer time for implementation is essential as cosmetic products have long shelf lives and hence, sellers need sufficient time to adapt their product inventory accordingly. The law applies exclusively to food and cosmetic product with the purpose of sale, meaning it does not apply for example to giveaways. What does the new packaging regulation in China entail and how does it affect enterprises?

China tackles excessive packaging

The new packaging regulation in China considers excessive packaging as the sum of 1) packaging void ratio, 2) the number of packaging layers and 3) the packaging cost.

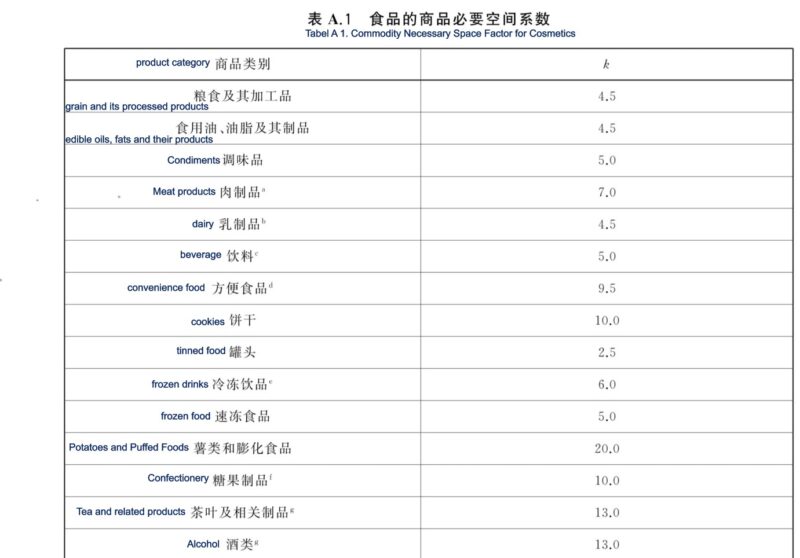

- Void ratio means the volume of the product in relation to the volume of the total package. The regulation defines different void ratios depending on the volume of the net product. For instance, if the product’s volume is between 5 and 15 mL in volume, its void ratio must be below 60%. The bigger the volume of the product, the lower the void ratio. Products above 50 mL volume may not exceed a void ratio of 30%. However, the law also delivers a specific formula to calculate the void ratio when other factors such as the spatial coefficient for commodity must be considered. The spatial coefficient for commodity (k) is the correction factor for the space required to additionally protect food and cosmetic products. Based on the formula which includes k, sellers can calculate their void ratio in detail. An appendix defines the corresponding k for all food and cosmetic product categories.

For example, eyeliner and lip products have a relatively large k (20.0), while dairy powder a rather small one (3.0). The law also provides three different measure techniques to assess the relevant volume as well as instructions on how to calculate correctly.

- The number of packaging layers refers to the number of covering materials physically detachable from the package, where the first layer touches the product and the outermost layer is the Nth layer. Grain and its processed products must not exceed three layers, other commodities are limited to a maximum of four layers.

- As for the packaging cost, it may not exceed 20% of the price of the product.

Furthermore, the law limits the sample quantity to one unit only. The law, however, neither mention any punishment when brands fail to adhere to new regulations nor indicates who is liable for the non-compliance of the packaging.

Does the Chinese packaging regulation meet international standards?

Compared to developed countries in Asia as well as in Europe, the new packaging regulation in China is still at its infancy and hence, has room for improvement. As our project leader Steffi Noel noticed, while there is no mention of penalties in the Chinese packaging regulation, a fine up to USD 2,489 can be imposed in Korea for violating the packaging standards. She also added that when looking at the packaging cost, Japan does not allow the cost to exceed 15% of the product’s selling price (vs. China’s 20%).

In Europe, the EU defines in the legislation “Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive” (PPWD) the standards for packaging waste and requires its member states to pass laws accordingly. The document was issued in 1994, is currently under review and a new legislative proposal is expected this year. Three major differences compared to the Chinese packaging regulation can be identified: the PPWD does not solely focus on food and cosmetics, it is much longer and sophisticated and its focus lays on specified standards for recyclable, reusable and recoverable packaging rather than layers or packaging cost.

Differences between Germany’s and China’s packaging regulation

Germany, which implements EU’s regulations in form of a packaging waste law is a good example to display the early stage of development of the new packaging regulation in China. The law includes all packaged commodities and focuses on recycling ability and recycling quota of the packaging. Who sells a packaged product must register the packaging in a system and get a license. Along with many other requirements, sellers are responsible for their packaging to be recycled according to law, and they must provide separate documentation as evidence that they can do it. A committee essentially proves the license eligibility, and a violation will be fined. Different stakeholders within the supply chain must license their packaging separately. In short, contrary to the Chinese packaging regulation, the German packaging waste law assigns liability throughout the whole process, implements penalties for any violation and targets the variety of packaging waste in a multifaceted way. The degree of sophistication evidently contrasts with the new packaging regulation in China.

What challenges does the industry face?

The new packaging regulation in China confronts enterprises with having to change Chinese consumers’ mindset and for some it even means to rethink their business model. Our project leader Steffi Noel explains that excessive packaging in China often symbolizes luxury. It represents a high-end product and is part of the unboxing experience. For many cosmetic products, packaging is one of the consumers’ evaluation indicators. Steffi Noel says that brands may lose certain customers when excessively beautiful packaging is missing. A lack of excessive packaging can also be perceived as cheap among Chinese consumers and is therefore not considered suitable to buy as a gift. In other words, the Chinese packaging regulation is going to cause a reduced desire to consume certain products. Smaller quantity sold is going to have a negative impact on sellers’ revenue.

Moreover, as part of this mindset products with excessive packaging can justify a higher price. Take Ming Qian Mao Feng tea as an example; An ordinary bag of 500 grams costs approximately 400 yuan. Wrapping it in an extravagant package such as a gift box can increase the price to 600 yuan creating a larger margin for sellers. Hence, when limited in their possibilities of excessive packaging, sellers’ revenue may decrease. As a result, enterprises are challenged to transform consumers’ mindset and find alternatives to substitute the unpackaging experience. They now must create an environment where packaging does not define the standard and perceived quality of the product, instead actual value and quality of the product will need to be prioritized. In this, the challenge will also be to communicate this message successfully to Chinese consumers.

Last, Steffi Noel suggests that in the short term the packaging industry may suffer from increased unemployment rate. This is because the demand for packaging decreases and packaging companies will therefore not need as many workers as before.

What opportunities are created with the Chinese packaging regulation?

The new packaging regulation in China creates room for new enterprises to be formed and existing ones to develop and flourish. The regulation incentivizes the food and cosmetic industry to prioritize improving the quality of their product. Previously invested money into packaging can go towards the actual product. Steffi Noel points out Jiang Xiaobai, a Chinese baijiu brand, as an example: having removed unnecessary packaging, the brand focuses on the quality of baijiu by constantly upgrading its brewing method. She says, “now, its new product, Golden Cap (金盖), one of the “light bottles of wine” type products, presents a pure and refreshing taste, while maintaining the [original] taste of Chinese baijiu. This initiative to reduce excessive packaging and improve product quality has attracted consumers’ attention and has been well received by them.”

Moreover, companies can leverage the new regulation within their marketing. As Chinese consumers increasingly consider sustainability and eco-friendliness as important element of their evaluation for consumption, brands can actively publicize how green their product and packaging are. This can additionally serve as an advantage point to brands already providing high qualitative and green products which can be utilized accordingly. Next, while in the short term packaging industry may encounter increased unemployment rate, in the long term, the industry will adapt and there is even an opportunity for new packaging companies to emerge. New packaging providers can innovate elegant yet green packaging which meet the requirements of the new packaging regulation in China and still catch consumers’ attention. Last, the change is a chance to co-opt the private sector in the responsibility to educate consumers about reducing their personal packaging waste.

All in all, the Chinese packaging regulation is a step in the right direction towards reducing waste in China. Yet, there is room for improvement. We will have to wait and see how the regulation is going to be implemented and enforced as well as what role product owners, consumers and the government will assume.

Author: Lucia Toth