How China started to measure trustworthiness of businesses

At the beginning of the 21st century the Chinese government began to make systematic use of new mediating technologies to measure the trustworthiness and financial creditworthiness of individuals and businesses. Establishing an online financial credit system was seen as key to better integrating China into the global market economy. The first credit-scoring companies were established in the 1990s, and following this the People’s Bank of China (PBC) established an enterprise and personal credit database. While initially focused on financial aspects like loans, the system was extended to the measurement of personal and corporate trustworthiness in relation to contract fulfillment and legal commitments. Discontent with widespread corruption in private and public institutions and with fraudulent company practices officially encouraged the Chinese government to launch a plan in 2014 for a full-blown national social credit system (SCS).

The “Planning Outline for the Construction of a Social Credit System (2014–2020)” focuses on restoring trust and improving ‘sincerity’ in government, commercial and societal affairs. Furthermore, it aims on raising judicial credibility and the ‘honest mentality and credit levels of the entire society’, with international competitiveness and a ‘harmonious Socialist society’ as the ultimate goals. Hence, the system isn’t only directed at citizens, it also targets businesses, and the Chinese government itself.

Does China’s social credit system seek to address the issues within the market?

The current legal system of regulatory checks and balances guiding the Chinese market is weak. There is widespread rule-breaking in areas such as IP violations, contracts, environment, labor violations, tax, and scams and fraud. As a result, this has fostered a low-trust market environment.

To address these issues, China’s social credit system seeks to set up a regulatory architecture to gather data on people and companies to define and determine trustworthiness. This serves as an info-intermediary to inform the government and regulators, and to grade all players within the greater business ecosystem such as companies and the public so they can take action. And lastly, to turn these data gathered insights into actionable and legitimate determinations that either restrict market access to those who don’t follow the rules, and to improve market access for those who do.

How does the social credit system help execute the government’s plan?

For China’s social credit system to work effectively there needs to be data interoperability between businesses, the local government, and Beijing. At present no single government agency has enough data or power to carry out the tasks detailed by the SCS alone. Therefore, the social credit system was created to bring all of China’s state agencies together to share data and cooperate in restricting market access to rule-breakers. It is made up up three interconnected components: a master database, the blacklisting system, a punishment and rewards mechanism. Beijing seeks to use these three primary components in conjunction to guide China through the next phases of development.

Connecting data across all state agencies: How it’s collected and where it’s stored?

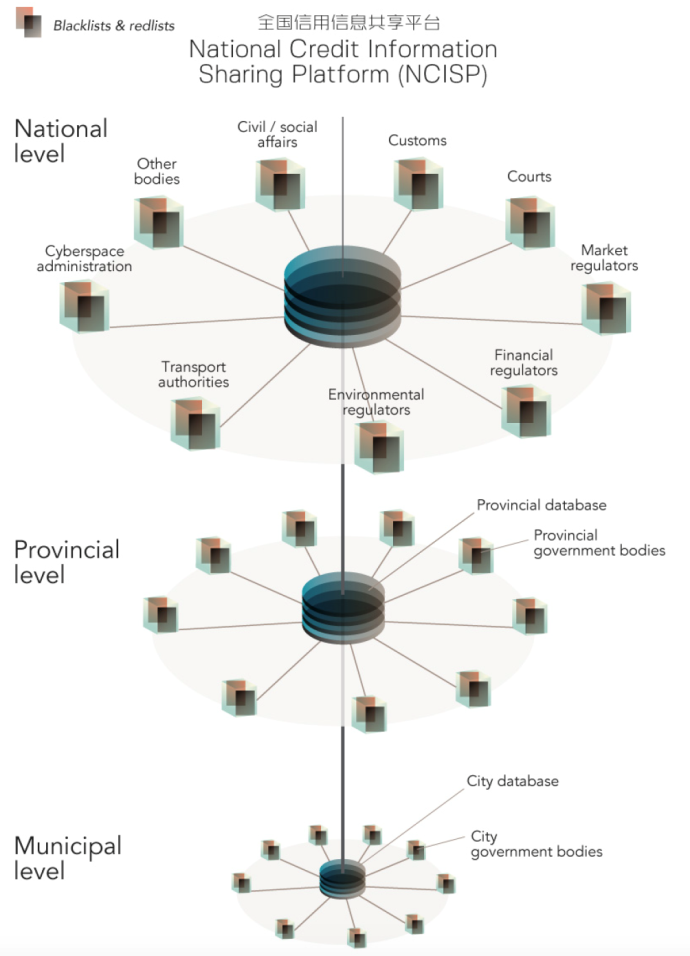

To solve the issue of data interoperability, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) created the National Credit Information Sharing Platform (NCISP) (全国信用信息共享平台). The NCISP is controlled by the central government and is the primary clearinghouse for social credit files on individuals and corporations. Government documents lay out in great detail exactly which records the central database will contain, which government agency will contribute which datasets, as well as which records will be open to the public and which won’t.

The NCISP is divided into 3 groups, with the top at the national level, the middle at the provincial level, and the municipal at the lowest level. In looking at the diagram below created by Trivium China, each center node is surrounded by a wide range of societal institutions, government bodies, and business organizations, with each having its own database, ratings standards, and blacklists. Data flows from the outside nodes to the center, and then from the center node up to the higher levels of government. Therefore, it is no wonder why pulling together this data, both structured and unstructured would lead to issues of interoperability. And as a consequence, may lead to legal errors, system inefficiencies and bureaucratic irresponsibility.

[Source: Trivium China, National Credit Information Sharing Platform]

Relevant authorities for implementation and enforcement

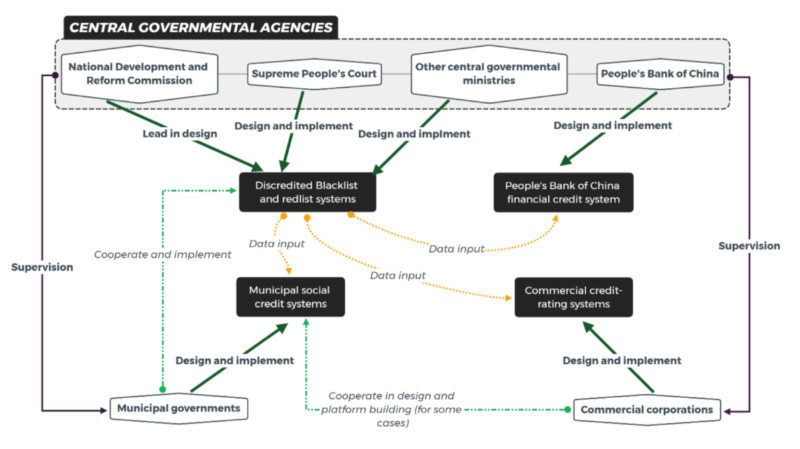

The National Development and Reform Commission and the Central Governmental Agencies designed the national discredited blacklist and credited redlist system, constructed the cyberinfrastructure to publicize information, and built the multi-agency joint sanction cooperation to punish discredited people. Yet it is mostly the local governmental agencies that implement these policies by collecting and uploading data, classifying and punishing people. Interestingly, many local governments also construct their own municipal SCSs and reconfigure the meaning of “trustworthiness” and “credit” in their local practice. Unlike the severe fragmentation among different agencies in the central government, local governmental authorities can better coordinate (or force) different departments to work together at the local level.

While there is still no cross ministry SCS agency at the central governmental level, municipal governments will commonly establish a new municipal governmental agency, for example, often with the name “XX SCS center/office,” to design and implement municipal SCSs. Although some cities’ municipal SCS for businesses are divided according to the different social fields under different governmental jurisdiction, the municipal SCS for individual persons is always united into one system on the local level. (See figure below for further details on the SCS for individual persons).

Thus, the system is very intricate, with a multitude of players seeking to govern a field while simultaneously designing, implementing, supervising, cooperating, and inputting data into various systems and labelled blacklists. When different actors in different industries and professions bring their own formulas to solve the problem and contribute to the system there results in a lot of position overstepping and mismanagement.

[Relationships among social credit systems for natural persons in China]

China’s social credit system is a merging of technologies

China’s social credit system is run by the state. But its development and functioning relies heavily on close cooperation with big Chinese internet companies like Alibaba, Baidu, Tencent and SenseTime. These provide technical infrastructures, and mine and process huge amounts of data harvested from countless sources and data-points, including geo-location and online payments. Simultaneously, the government is constructing several national data platforms for collecting, storing, sharing and mining population data with a focus on ‘integrating these separated platforms into centralized data infrastructures.

For example, one of the more famous and widely used apps Alipay has a form of credit collection, namely the Sesame Credit score. In practical use, Alibaba has begun to leverage the app’s popularity to try to solve a conundrum such as the lack of trust between buyers and sellers online. In 2016, Alibaba signed another data-sharing MOU with the central government, promising to expand its involvement in meting out penalties and perks. Agreements like these between China’s digital ecosystem strong players are only the beginning of a slow integration between the SCS and the world of e-commerce and digital payment.

Although some commercial companies, such as Ant Financial and Liulian Technology (Shenyang), helped different governmental agencies to build their own SCS models or cyberinfrastructures, there is no evidence that commercial SCS data is included in any municipal governmental SCS calculation to date.

[Source: Alipay Screenshot, Ant Financial’s credit system]

How do businesses search for information on companies and punishment measures?

Businesses can find all related information regarding the SCS on the NCISP. Below are translated examples of what the menu looks like when performing a “search” for registered companies using their social credit numbers on the platform. A searcher can begin by choosing a city or by company SCN. Furthermore, by scrolling alongside the left side menu, you can see the respective ‘punishments’ the SCS is responsible for to companies who break the rules. As you go down the list the punishments become more severe. They go from listing an entity as merely partaking in an abnormal operation to labeling it a “dishonest entity.” Then from exposing companies to random checks to handing out administrative punishments, freezing assets, and on to sending out cancellation notices for business closure. And lastly, to being blacklisted. Thus, the repercussions for all businesses in China are not to be underestimated.

[Source: National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System website, China’s corporate social credit system website explained]

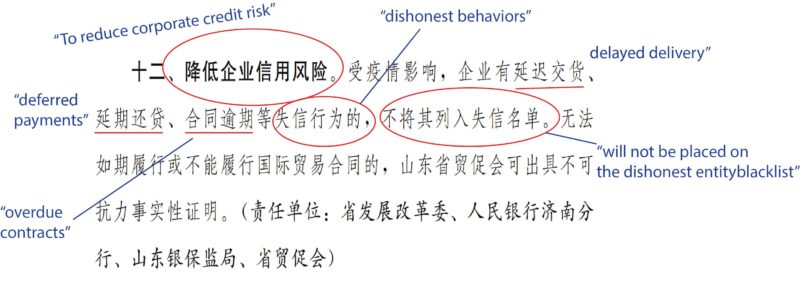

To provide a case example of how the SCS works, recently there was an announcement from the Shandong Provincial People’s Government. It reported that to “reduce corporate credit risk” (降低企业信用风险) during the current Coronavirus (nCoV) crisis, enterprises with delayed deliveries, deferred payments, overdue contracts, and other dishonest behaviors will not be put on the dishonest entities black list. Below is a translation of the text, which is declared on the 12th measure.

[Source: Shandong Provincial People’s Government]

What companies need to know about the blacklists and redlists

The “blacklist & redlist” mechanism is widely used across different sectors to build the social credit system. A blacklist is a public record of companies (and individuals) found in serious violation of existing regulations. A redlist is the opposite – a public record of companies (and individuals) that have been consistently compliant. Blacklists are for entities with adverse credit information and redlists are for entities with good credit information. Important to note is that insofar blacklists are not yet centralized, but rather the state, provincial, municipal and local agencies manage their own blacklists. The primary focus of most of these blacklists is on the regulation of malpractice in the business environment.

How Blacklisting Works?

- Step 1: State agency determines the company is non-compliant

- Step 2: State agency puts the company on a blacklist

- Step 3: The blacklist is sent to the NCISP and included in the company’s social credit file in the master database

- Step 4: Other state agencies get access to the blacklist

- Step 5: The public can see blacklist data as well

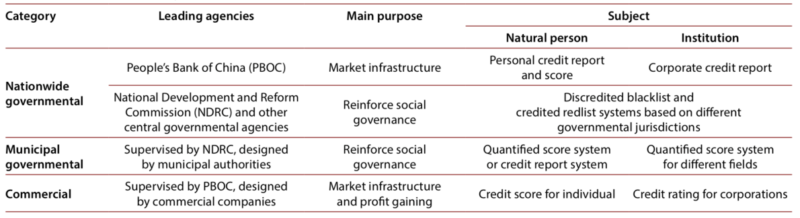

The system for blacklisting is very complex and organized by different agencies and by different levels of government. Below is a table chart which outlines some of the categories, leading agencies, and purpose and subject of their blacklisting mandate.

[Leading agencies involved in China’s social credit system blacklisting system]

Here are a few ways in which companies can be put on the blacklists

- Not honoring legal obligations

- Failing to pay employees

- Fraudulent financial activity

- Tax evasion

- Import-export offenses

- Endangering public health and safety

However, this list is set to get much longer as regulators in the fields of medicine, travel, education, sports, agriculture, e-commerce, energy, and others start to create and hone their own lists to discourage behavior like:

- Excess energy consumption

- Polluting the environment or endangering ecology

- Operating without the right licenses

- Safety violations and accidents

- Counterfeiting, fraud, and IP violations

- Poor production quality

Redlists are structured along similar likes as blacklists: there are a few big major redlists at the national level, and then a whole series of local redlists at the city and provincial levels

What is in China’s Corporate social credit system?

- Basic company registration data

- Braches/Subsidiaries

- Executive-level personnel

- Annual Reports

- Social insurance payment history

- Provident fund deposit history

- Administrative licenses

- Administrative penalties received

- Inspection records

- Awards and honors

- Utility payment history

- Red and blacklist records

- Equity structure (shareholders, legal representative, stock info)

- Tax information (taxes paid and owed, tax rate, tax period, etc)

Important to note is that most of the data from above do not come from high tech sources, but rather are derived mostly from the records generated in the course of your business operations such as customs, tax, and utilities. Furthermore, regarding the data above, some of it is self-submitted, like the annual reports and details of personnel. So in essence, there currently still remains a small level of control.

Social Credit Score components for companies

There are five ancillary aspects of the SCS that only apply to companies and organizations.

- The National Credit Information Publicity System

- Unified social credit numbers

- Company grading systems

- The new random inspection system

- Credit commitment letters

The National Credit Information Publicity System

Corporate social credit records are available to the public via the National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System (NECIPS) 国家企业信用信息公示系统, a website which contains compliance data on any company with a license to operate in China, including local subsidiaries of foreign companies. NECIPS’s public records include information on key shareholders and personnel, operational licenses and permits, inspection results, notices of company dissolutions, notices of frozen assets, operational irregularities, and any past violations.

NECIPS is set to become ground zero for corporate due diligence, and will be a key resource for companies to monitor the state of their own credit records. But the site is more than just a clearinghouse for data discovery; it’s also a data management portal. Company representatives can sign up for an account and upload basic company data and annual reports.

[Source: China’s enterprise social credit publicity system screenshot]

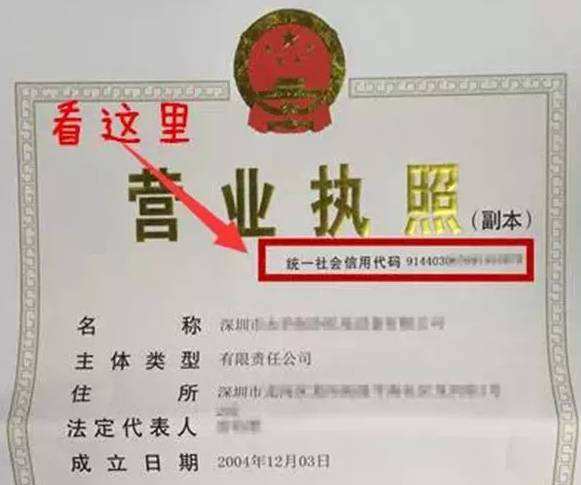

Unified Social Credit Numbers

In 2015, as a preliminary stepping stone to implementing the enterprise social credit system, the central government began assigning a new code – the Unified Social Credit Number (统一社会信用代码) – to each domestic company and organization. The USCN has now replaced traditional business license numbers on business registration certificates as the primary code by which an enterprise is identified. A USCN can be used to search for information on any China-registered company the National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System.

[The Unified Social Credit Number is circled in red]

Corporate grading systems

As we’ve seen in previous sections, under China’s social credit system, market regulators will treat companies differently depending on their social credit record. Companies with good social credit will enjoy simpler bureaucratic processes, decreased inspection rates, and other perks. Companies with poor social credit may have higher taxes, be subject to more frequent inspections, be barred from participating in government procurement, and other repercussions.

The determination of who has good credit and who has bad credit will largely be based on four different types of grades that companies will receive: Comprehensive Public Credit Rating, Operational grades, Industry association grades, and Financial credit scores.

The new random inspection system

In 2015, Chinese regulators took a step towards cracking down on corruption by implementing a new safety and production inspection system called “Double Random, One Open” (双随机,一公开), wherein both the company to be inspected and the inspector are randomly selected (hence “double random”), and the inspection results are openly published (“one open”).

[Double Random, One Open inspection system notification]

The government’s goal here was to standardize the timing of inspections so that inspectors can’t excessively target one company while ignoring another, and to standardize the inspection process so that inspectors don’t have as much discretionary decision-making power. While random inspections aren’t a core component of the SCS per se, the results of these inspections are publicized on the National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System website, and are included in a company’s social credit file.

Credit commitment letters

One of the most recent additions to the SCS is something called the “credit commitment system”, which was introduced in a national policy released in July 2019. The system encourages companies to sign standardized letters promising to operate in good faith and to honor social credit regulations.

Signed credit commitment letters are openly published on the National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System website and are included in the company’s social credit file. Companies with good credit who have signed credit commitment letters may have various bureaucratic applications pre-approved on the strength of their promise.

Myths & weaknesses of China’s corporate social credit system

The SCS is not a fully integrated and unified system, which is often the way it is portrayed in the West. In practice, the system is highly fragmented and technically complex, consisting of a variety of social credit initiatives and projects at the local and regional levels that will unlikely be fully integrated at the national level. The data is not high tech and new. Regarding the definition of trust. The idea that the social credit system will artificially increase levels of “intentional trust” may not materialize. Therefore, SCS may not address the actual underlying social issues. Lastly, there is high potential for abuse. If the system is built in such a way that it is open to abuse, allowing fraudulent companies to come away with good credit records, it will call into question the entire system’s validity.

Uneven implementation across industries

While it is clear that the SCS will eventually have ramifications for every company doing business in China, policymakers have placed a special focus on implementation in industries they feel are most in need of regulation. This has been particularly evident in the roll-out of Comprehensive Public Credit Grades, the central government’s new four-tier rating system for enterprises.

In September 2019, the NDRC announced the completion of credit evaluations on 33 million Chinese market entities. To put that into perspective, there were 34.7 million total companies registered in China in 2018, so the evaluation covers most registered companies in the market. But only a tiny portion of those results have been made public. Furthermore, these ratings have not been incorporated into any of the searchable, centralized platforms, but published in Excel spreadsheets. Also, there has been no word on whether or not these grades will eventually be added to, and viewable via, the main public portals.

Data dispersion

Two main platforms were created to serve credit data to the general public: the Credit China website and the National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System (NECIPS). But data sharing between the two is patchy at best, with records that appear on one often being unsearchable on the other. Making matters worse, several state agencies host their own credit data platforms with equally poor interconnectivity, haphazardly transferring data from and sharing data with NECIPS, Credit China, and each other.

Boundaries of the system aren’t clearly defined

Social credit policy at the national level has encouraged provincial and city governments to extend the system by developing blacklists, rewards, and punishment schemes for their own jurisdictions. But policymakers are very much aware of the social credit’s potential to exceed its own mandate. Deputy Director Meng Wei stressed that social credit must have a clearly defined legal basis, and outlined the “Three Prevents”:

- Preventing credit record data collection from expanding beyond reasonable and appropriate boundaries.

- Preventing the unauthorized creation of blacklists and related punishments.

- Preventing the unauthorized or illegal applications of the credit system.

What we know

- China’s corporate social credit system will be used more broadly to regulate the commerce sector. In June 2019, the State Council released a guidance document that calls for establishing three components — a credit commitment system, a credit report mechanism, and a classified credit regulation — as the basis for inspecting businesses.

- China has already built credit profiles for 33 million enterprises and organizations, including foreign companies. By some estimates, over two-thirds of China’s regional governments have released or are in the process of releasing local social credit initiatives.

- Companies will be evaluated based on compliance with their specific industry regulations.

- There is no set of blanket standards guiding how companies will be evaluated. Instead, China’s central and local governments have published a total of 1,500 documents defining over 300 rating requirements for companies in different industries, but several have yet to be released. Understanding exactly which types of criteria companies will be evaluated on will be crucial to maintaining a healthy score.

- Companies can land themselves on both a blacklist and a “red list.” So far, China has compiled a total of 51 blacklists for non-compliance with laws and regulations.

- The blacklist for the commercial sector has been divided in two parts: the joint credit punishment list for dishonest entities, which restricts a company’s direct sales and commodity quotas, and the special attention list, about which not much is known other than companies that find themselves on the list will face “stricter regulations.

What we don’t know

- What the rating system will look like? Recent policy documents have made mention of a “Comprehensive Public Credit Rating” (公共信用综合评价) which is a national corporate credit evaluation that will determine how companies will be treated depending on their social credit scores. But exactly what the rating will look like, and how much it will matter, has been unclear.

- It is unclear how the national-level rating system will synchronize with the various rating systems developed by local governments and industry regulators, whose ratings will also be taken into account in the comprehensive evaluation of a company. But, it has been reported that while the national-level rating will serve as a foundational metric, city and provincial-level ratings will take priority.

- Can (and how fast will companies be able to) get off of a blacklist?

In summary, there are many questions to be answered. Like, will there be a meta-score based on all the available ratings for every company? A standardized system for the types of treatment companies will receive based on the results of their evaluations? How the algorithms will calculate the score? Will it be immune to biases against foreign companies? Strategic industries? However, the draft PRC Social Credit Law might answer some of these questions, but for now, the timeline for this legislation is unclear.

What does the enterprise social credit system mean for companies operating in China?

Carrying out the above steps will bring a company up to date and position it well to effectively manage the effects of the Corporate SCS. However, as the System continues to adjust, expand and improve, companies need to stay on top of further developments. An effective monitoring system that provides companies with the ability to react quickly needs to cover two dimensions. First, the close observation of government-side changes to ratings and rating requirements. Second, the internal monitoring of business operations with regard to the sustained fulfillment of, sometimes changing, requirements. This will necessitate regularly checking a company’s rating scores across all ratings and the monitoring of entries about the company in the different databases.

How to prepare for China’s enterprise social credit system

Every company in China, regardless of size or ownership structure, needs to expect that all its operations in the Chinese market are in one way or another, either via scale ratings or compliance records, tracked and recorded by the mechanisms of the Corporate SCS. However, the implementation status of the Corporate SCS, and with it the intensity of data transfers, tracking and recording, still varies between different industries and locations. Most of the key industries that are front-runner industries with regards to the System, meaning the coverage of the ratings is already far advanced, includes the automotive and chemical industries, as well as the entire logistics industry. Foreign business invested in these sectors will need to prepare.

Early and thorough preparation is the key for companies to tackle the challenges of the Corporate SCS. With enough preparation, companies will avoid being surprised by the accelerating implementation of the ratings, or suddenly being faced with a rating downgrade, or even a classification as a distrusted enterprise, followed by all the potentially severe consequences.

The corporate social credit score system is likely to have a huge impact on China’s business environment. Any company whose operations extend into the Chinese market must invest in understanding the SCS and its potential to impact their operations, as well as how to engage with it to minimize risk.

For those already active in the market, taking a stand still and “wait to see how the system develops” is the wrong move. Companies need to be proactive and begin creating an internal mechanism for tracking the system’s growth and impact.

What to keep in mind

- Understand exactly what the system requires from your company

- Assess where your company stands regarding the requirements

- Design and implement effective adjustments

- Continuous monitoring

- Exchange with government authorities

Author: Jeffrey Craig

Let China Paradigm have a positive impact on your business!

Listen to China Paradigm on iTunes