Modern-day China has a rapidly growing wine and spirits market, with even some of the world’s most prestigious names like Château Lafite Rothschild taking root in China. But this market didn’t arise from China embracing Western drink products and consumerism, nor does it come from China’s rapid globalization and economic development over recent years.

In fact, China has a rich and complex history with alcohol, with long-established traditions and etiquette when it comes to alcohol consumption. This form of consumption is usually social or celebratory and has historically been an integral part of Chinese culture. The implication and way of drinking have also changed with the newer generation and a cultural shift in social norms.

Download our China F&B White Paper

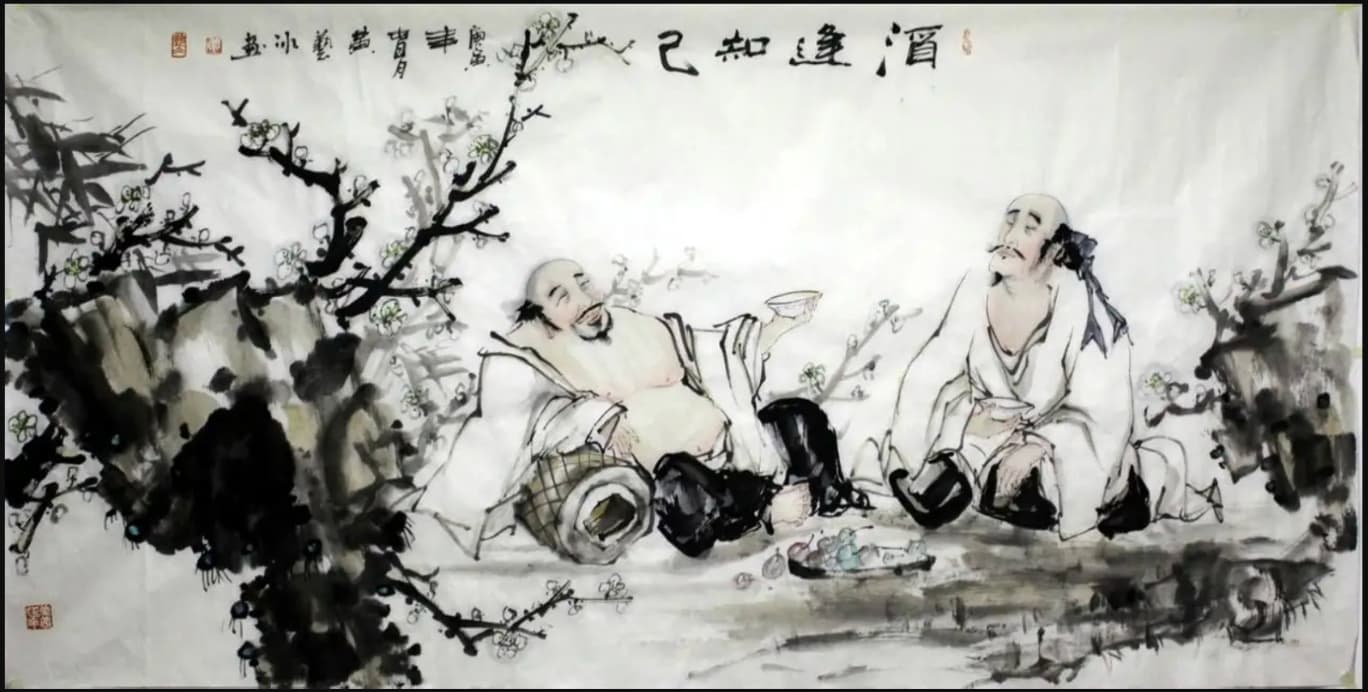

The famous Chinese proverb, “酒逢知己千杯少” (Jiǔ féng zhījǐ qiān bēi shǎo), translates to “with a close friend, a thousand cups of wine is far too little”, accurately depicts traditional Chinese drinking culture and the role that alcohol has in forming and maintaining social relationships. Drinking has always been the way to actively build relationships in Chinese society and culture, whether this is with friends, family, partners, or even professional relationships in the workplace.

This means that drinking in China is appropriate during group meals and other social group events, such as KTV, business functions, weddings, birthdays, etc. Alcohol is also used to celebrate special occasions, like the Chinese New Year/Spring Festival, the Mid-Autumn Moon Festival, or even weddings and birthday banquets. People gather around tables with family and friends and enjoy good food while drinking alcohol together.

Chinese drinking etiquette: How to properly “Ganbei”

Chinese drinkers will convey cheers by saying “Ganbei” (干杯) to their friends. The literal translation is “empty cup,” which is used to encourage guests to finish their entire glass. It’s considered rude not to at least take a sip when someone is offered a toast, but it is not necessary to finish the entire beverage (though it would be much appreciated).

Basic rules when making a toast in China

Most meals with alcohol in China usually start with a toast, and it can be considered rude to start eating or drinking before the entire group has had their beverages and food prepared. Moreover, while this can vary between social settings, it’s generally impolite to drink before the host makes a toast. Usually, the first toast should be an “empty cup” as a sign of respect and as a way to start the meal or event. However, this applies more so to drinks served in shot glasses (generally spirits such as baijiu, sake, etc.).

When making a toast, people usually use the right hand as a sign of respect, and to keep their glasses at a lower position than others (especially the host). For extra formality, the left hand can also be placed underneath the cup while it is being held by the right hand. The proper way to receive or offer a glass of alcohol is always with both hands.

Drinking etiquette and hospitality in China also mean that a guest’s glass will probably never be empty. It’s a custom for the host or friends to automatically refill each other’s glasses to the brim whenever it’s empty or a toast has been made, even when it is not requested. In general, younger drinkers should be refilling the glass of those who are older or outrank them (boss, more senior friend, an older family member, etc.), but this isn’t a very strict rule when going out with a group of friends.

How can one remain relatively sober despite all these drinking pressures and rules?

Refusing to drink more will be easier if a guest establishes their limitations at the beginning of the meal rather than midway. One can politely say “我酒量不好” (wǒ jiǔliàng bùhǎo) to express a low capacity for alcohol intake, or give some sort of excuse in advance (not feeling well, having an early morning the next day, health problems, etc.). Some people will also physically cover their cup with a hand to stop an over-hospitable host who wants to keep the liquor flowing.

A key feature of Chinese drinking culture: Alcohol in the workplace and modern pushback

Surprisingly to some foreigners, alcohol also has a very prominent role in Chinese professional culture. This refers to work banquets, networking events, client dinners, and anything with a social element.

Drinking at work can also be great for networking, with respectful toasts to important clients and executives allowing employees to interact with those higher up on the corporate ladder. However, the Chinese workplace drinking culture has seen its fair share of problems in recent years. In August 2020, an employee of Xiamen International Bank refused to drink and was slapped by his supervisor for it. Women are even more vulnerable in these scenarios, as two female employees of Didi Global Inc. and Alibaba, respectively, reported cases of sexual assault by clients and superiors after heavy professional drinking.

What alcohols are popular in China?

Baijiu is the most popular alcohol in China, made from sorghum, rice, or wheat, and contains very high alcohol content. The most famous premium baijiu is Kweichow Moutai, which was sold at Sotheby’s for USD 1.4 million for 24 bottles in 2021.

Red wine, brandy, whisky, and spirits such as tequila and vodka have also been gaining popularity, with demand for spirits generally growing amongst younger consumers.

Some other popular drinks in China are beer and cocktails, which are gaining popularity amongst the younger generation. Due to Western influence, there isn’t a shortage of bars with modern and innovative drink recipes in China.

Wine culture in China

The people of China have been drinking wine for over 3,000 years because of the country’s rich history with grapes and other produce like plums and peaches (which also lend themselves well to becoming alcohol). As such, there are currently over 50 types of grapes used in Chinese winemaking—some blended together while others remain singularly varietal—and this number continues to grow each year as more varieties become available thanks to technological advances in winemaking.

Historically, wine has been tied to art and culture. The famous calligrapher Wang Xizhi of the Eastern Jin dynasty created his greatest work while drunk off of wine, and failed to surpass it while sober. A number of ancient poets like Li Bai and Han Yu have all written about wine and the act of creating art with wine.

Red wine’s popularity in China might also be due to its auspicious red color, a predominant lucky color in Chinese culture. Traditional Chinese Medicine also believes that red wine provides some health benefits, making it a healthier alternative to baijiu.

Food pairings are often found in China’s bars and pubs

Along with alcohol, food pairings have also evolved with time and cultural shifts. For many, the go-to pairing with Chinese food is tea. The challenge of pairing Chinese food with a certain type of alcohol is difficult because of how many different categories of Chinese food there are.

For many of the bars in China, consumers can find both Western and Chinese food, depending on the bar. Some menus will have traditional Chinese side dishes like dim sum, dumplings, and crispy duck, while other, more Westernized pubs will have sliders, fries, and other appetizers. This has to do with the evolving night scene in China, as bars are incorporating some traditional street food elements into their stores in the menu and decoration. Other bars lean more into the Western style to appeal to both local and global consumers.

Bars in China

With more and more Gen Z customers going to bars, the drinking scene in China has transformed into a space for activities like card game playing and studying.

There is also this concept of themed bars in China that often revolves around a popular social media trend or is based on a movie/TV series. The interior of these bars is built to transform consumers into a different world, alongside themed drinks that often require creative ingredients that draw a lot of attention on social media.

For example, there is an MBTI bar based in Shanghai, China, that matches consumers’ cocktail flavor to their personality based on a test. The purpose behind these bars is to gather a community of people together and to drink to create a good experience, rather than drinking to get drunk.

Drinking etiquette cheat sheet

Chinese drinking culture is complex and one of the most important aspects of Chinese social life, as it has been for centuries. It’s important to recall that alcohol is used as a way of building relationships, which is why the Chinese drink so much. Alcohol is also used to shape business relations, and one’s drinking ability has a very real impact on outcomes in the corporate and professional world.

- It’s rude not to drink if someone offers you a toast.

- Both hands should always be used when giving or receiving a cup.

- “Ganbei” is used as “cheers,” but literally translates to “empty cup” and is used to encourage friends to completely finish the cup.

- Alcohol consumption can be used as a measure of hospitality and friendship. So, it’s important to be tactful with one’s words when refusing a drink.

- Drinking has shifted from getting drunk to an experience with the rise of themed bars.

- There are many different food pairings that go with alcohol in China, where you can find both Chinese and Western side dishes.